By Michael Karadjis

Originally published August 11, 2025 at https://theirantiimperialismandours.com/2025/08/11/slaughter-on-the-syrian-coast-ruthless-insurgency-meets-horrific-pogrom-massive-hole-in-syrian-revolution/

The investigative commission report into the March massacre of the Alawite citizenry, set up by the Syrian government at the time, finally turned in its findings on July 10, four months after it was launched. Claiming some 1400 killings, it identified 298 individuals broadly aligned with government-led forces, and 265 individuals who took part in the initial Assadist insurgency, as alleged perpetrators of these killings and other violations. I first held off publishing this report – much of which I wrote months ago – due to the difficulties of establishing facts from afar, but then as time went on decided to await the investigative report. However, as I publish, while press conferences have been held, the government has still not made the report public, though we are aware of its broad outlines, so I am releasing my understanding of the situation now; if and when it becomes pubic, I am happy to be proven wrong on any points; or to acknowledge that the investigation did not live up to expectations. Late Update: the UNHCR Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic has also finally released its mammoth report, with a huge amount of detailed information.

This is a huge report which I have put together over months. Please don’t complain that it’s too “lengthy.” It is not an essay. In writing this report I am also compiling a huge amount of material. Please treat it as a resource rather than a quick read. There is a bibliography, including main reports, at the end.

Michael Karadjis

Contents

- Introduction

- The Assadist Insurgency

- The Syrian government’s security response – and the sectarian pogrom

- Disinformation overload

- Syrian government reaction

- Arrests

- Who was responsible for the civilian massacres?

- The General Security forces (GSS): Reportedly the most ‘disciplined’ and ‘professional’

- Military ‘factions’, ‘foreign jihadis’, ‘Amshat and Hamzat’ – Heavily reported as responsible for massacres

- However, some military brigades acted with integrity

- Armed civilians and “revenge” killing

- Assad regime slaughterhouse: Incubator of sectarian mayhem

- The initial ‘fairy-tale’ and its abrupt ending

- The unfolding deterioration of the situation from December to March

- Causes of this deterioration of the Alawite situation

- What now? The evolution of the al-Sharaa government

- What needs to be done?

- Bibliography

Introduction

While the Assad regime’s tyrannical rule always contained an unofficial sectarian element, it was only when it came under threat from the people’s revolution in 2011-12 that it made a deliberate decision to sectarianise the conflict on a truly massive scale; Syria turned into a gigantic laboratory of genocidal sectarian engineering, cleansing and massacre. The large-scale sectarian massacres of Alawite civilians over March 7-8, which took place in response to the attempted coup and slaughter of security forces and civilians unleashed by Assadist officers on March 6, demonstrate that the impacts of this policy are ongoing and have boomeranged horrifically against innocent civilian members of the sect that the Assad regime’s rule was based among.

The medium-term impacts of these events are difficult to fathom. Just three months after the glorious revolution against the genocidal regime, characterised precisely by a total lack of revenge, either sectarian or directed, it seems the Assadist coup leaders got what they wanted: a massive hole in the revolution, the alienation from the rest of post-Assad Syria of a large part of the Alawite population now multiplied a thousand-fold. Whether some of that can be undone depends a great deal on what the government does next; but for a great many Alawi who were exposed to the slaughter, the ship has sailed; thousands have fled to Lebanon, thousands more just want to leave.

The Syrian government led by president Ahmed al-Sharaa ordered that civilians not be touched, condemned the massacres, set up a commission to investigate the events and bring perpetrators to trial, and made arrests, and rapidly expelled unruly elements from the region and brought the massacre to a close; the general security forces most directly under its command appear to have been the least involved and the most professional compared to unruly military factions, jihadi groups and armed civilians; propaganda claims that this was a massacre unleashed by the government of “HTS” (which no longer exists) or “al-Qaeda” (which Nusra, the forerunner of HTS, quit in 2016) should be dismissed. Indeed, the UN Commission of Inquiry report “found no evidence of a governmental policy or plan to carry out such attacks” (p.18). Simplistic nonsense serves no useful purpose, though it was very useful to enemies of the new Syria, especially Israel, Iran and various other forces influenced by them.

Nevertheless, that does not absolve the government; the military and other forces that carried out this pogrom were theoretically under the authority of the government, so even though it appears to be mostly a question of massive indiscipline and government lack of control of newly patched-together military forces, in international law it still holds overall legal responsibility. The government was also initially slow to move with the level of urgency that the gravity of the situation required, though this can also be explained by being overwhelmed by such fast-moving events. There are more significant critiques that can be made of its handling of the situation beforehand, which I will touch on later. It is certainly valid to critique its apparent lack of interest in giving the issue the attention it needs since, given that nothing that has occurred since the revolution can be compared to the slaughter of a thousand or so civilians over a couple of days (declaring a day of mourning, for example, would have demonstrated some kind of genuine commitment).

Whatever the case, the future of the revolution – meaning not simply the overthrow of Assad and the ‘democratic space’ now open in Syria, but more broadly the revolution’s promise of a Syria for all its communities, a Syria that rejects the methods of the past regime – now depends on how real, how effective, how transparent, how just this process of identifying, trying and punishing the perpetrators is, as well as working hard with the Alawite community leaders for effective policies related to compensation, reconciliation and above all inclusion in the institutions of the new Syria, especially at the level of security.

I am not making any predictions about how real this process will be, and am interested neither in spreading illusions in the al-Sharaa government, nor of demonising it. Below is my understanding of the situation for now; I can’t guarantee every sentence is correct. Not being in Syria, it has been extremely difficult to get a clear understanding, with Syrians on the ground presenting a myriad of different, often sharply contrasting accounts. That’s one reason I have held off publishing for so long; most of this was written months ago. Nevertheless, I believe the below, and the analysis of the wider background, is fundamentally sound.

[As I publish now, in early August, last month witnessed a disastrous debacle in Suweida with a horrific massacre of the Druze population which suggests the government learned little from these March events; some would say it shows the government still has little control over some of its armed forces, while others would claim it proves the government is deliberately behind such mass violations in order to instrumentalise sectarianism to consolidate its Sunni base, kind of Assad-in-reverse; I have written of these events elsewhere, but it is impossible to do any justice to these huge events here].

The Assadist insurgency

The chain of events began on April 6, when hundreds of former Assadist officers, who had been hiding out in mountainous parts of the two coastal provinces – Tartous and Latakia – where Alawites predominate, with large quantities of weaponry, launched a coordinated ambush on Syria’s new security forces in the region, as well as attacking government buildings, hospitals, power plants, gas and oil companies and attempting to seize control of the region. They also severed an underground power supply on March 7, cutting power to most of Latakia.

According to the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM), the Assadists “targeted police stations, checkpoints, and cut the Latakia-Jableh-Baniyas main road, concurrently with attacks on the Naval Forces Command, the Naval College near Jableh, the Criminal Security branches in Latakia and Jableh, Al-Qardaha Regional Command, and Jableh National Hospital, taking full control of them. They also cut the Duraikeish Road, Al-Qastal-Latakia Road, the Beit Yashout Road, and Satamu Military Airport, in addition to seizing control of Tartous port checkpoints. At the onset of the attacks, these groups killed approximately 75 individuals, including members of the General Security, police officers, and civilians. Around 200 personnel were taken captive, and dozens were injured.” The UN Commission of Inquiry report however claims some 175 General Security officers (plus 22 earlier) were killed in these ambushes, plus 61 officers of the army Division 400 stationed in the region (p. 10-11).

Initial reports were that some 25 Sunni civilians were also killed, but later these figures were greatly multiplied, as over 200 civilians “including women and children, were killed in mass executions and systematic attacks targeting residential neighborhoods and public roads.” The first 15 civilians were killed by “gunmen targeting their vehicles on the outskirts of the city of Jableh” on Thursday March 6, according to reportage by the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), who further reported that “vehicles with Idlib license plates were deliberately attacked, and several victims’ bodies were burned inside them,” claiming at least 32 civilian vehicles were so targeted, as in the example of “Badr Hatem, his wife Walaa Saqr, and his son Ali [who] were killed by remnants of the former regime and their bodies were hidden simply because they were from Idlib Governorate.”

According to Omran in Syria Direct, a resident of Jableh where the insurgency began (and who vigorously condemns the pro-government military factions who later sacked the city), “While first storming the city’s southern neighborhoods, regime remnants carried out sectarian killings against the Sunni component.” The report by the well-respected SCM notes the same. This prompted “Sunni youth to announce a public mobilization in the city and pursue the regime remnants to stop them from taking control of the city. They broke the siege on hospitals that were besieged by groups affiliated with the former regime.” Another report claimed “The coup attempt started in Alawite villages (Beit Aana, Hmeimim, Qardaha), reaching Jableh’s outskirts. Hospitals were used as ambush sites against security forces and civilians providing aid. … By midnight 07/03/2025, regime militias took Umm Barghal checkpoint in the south, attacking Sunni homes & killing 7 young men. … By 07/03/2025 afternoon, 15+ Sunni martyrs had fallen.” This report similarly discusses the decisive role of Jableh citizens in resisting this opening Assadist attack.

While some have attempted to downplay the Assadist insurgency and slaughter as a virtual invention of the Syrian government in order to initiate a sectarian rampage, even this report by a local Alawite which indeed does blame the government, does somewhat downplay the Assadist attack, and describes the slaughter of Alawites in the most horrific terms imaginable, nevertheless states that “at least 120 of them [government security forces] were killed by regime remnants [ie, Assadists]. … A friend who had helped evacuate his Sunni relatives from Snobar, near Jableh, put it bluntly: ‘All the good ones have been wiped out’.”

Similarly, Christian activist ‘S’ who “works with both Sunni and Alawite communities,” describes the night of March 6 in Baniyas, where possibly the most terrible massacres of Alawites subsequently took place (cited in Gregory Waters’ Syria Revisited site):

“ … you could hear and see the bodies of General Security being brought to the hospital. I think 150 bodies of security forces were brought to the hospital in total [from the city and countryside]. Many Alawites here still deny that there was an insurgency, but then why was I warned that evening and how do you explain the killed security forces? After a few hours of the attack and taking over some neighborhoods, most of the insurgents fled. They realized there was no foreign intervention coming and they had been tricked by the regime media and leaders and had made a huge mistake.”

The leaders of the Assadist insurgency are well-known. On March 6, a statement signed by Brigadier General Ghiath Suleiman Dalla, a former commander in the Assad regime’s notoriously brutal Fourth Division, announced the launch of “the Military Council for the Liberation of Syria,” calling for “the overthrow of the existing regime” and “the liberation of all Syrian territory from the occupying terrorist forces.”

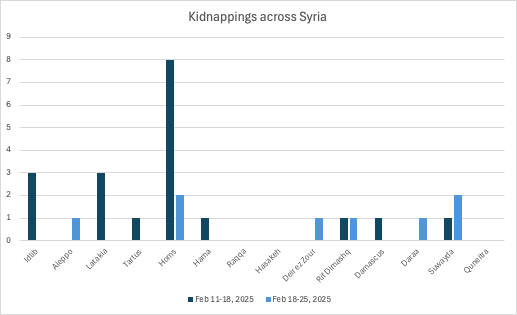

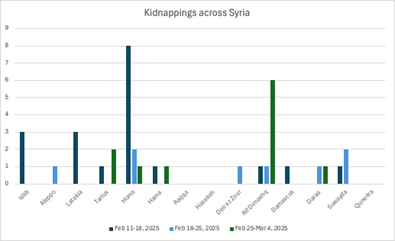

Declaration of the Military Council for the Liberation of Syria; Declaration of the Coastal Shield Brigade; Mohammad Jaber, in his Assadist days, top photo, and in the interview, below photos (middle)

Earlier, on February 7, another former Assadist military officer with a brutal record, Muqdad Fatiha, had announced the formation of the ‘Coastal Shield Brigade’, calling for attacks on government security forces. A series of killings of security forces increased throughout February and early March, leading up to the March 6 mass ambush. Another group are troops linked to Bassam Hossam Al-Din, a former leader of the Assadist Mountain Lions militia, who as early as December 11 threatened to launch an “Alawite military revolution,” and in January kidnapped and threatened to behead a number of security personnel. More recently, it emerged that yet another former Assadist officer, now residing in the United Arab Emirates, Mohammad Jaber, former leader of the Assadist Desert Falcons militia, was also involved in the insurgency, by his own admission.

The massacres targeted both security forces and civilians. In addition to the Sunni civilians targeted on a sectarian basis, it has been widely alleged that the Assadist forces also killed Alawite civilians considered ‘disloyal’ for refusing to support the insurgency. Indeed, Muqdad Fatiha himself released a video in early 2025 where he openly threatened Alawite civilians who had accepted the new Syrian government, or who had denounced his savage crimes: “Your punishment will be severe, boys and girls. I have your names and your social media accounts, I have all the information I need to find you. I’ll be coming to see you soon.” Interestingly, he notes that he has “no problem with HTS,” who “gave me amnesty and treated me well,” but “my problem is with you, my fellow Alawites.” He also confirms that images of him carrying out atrocities under Assad are real.

It is difficult to assess the degree of support among Alawite civilians for the Assadist insurgency. Reportage in the immediate weeks after the overthrow of Assad revealed how hated the Assad regime was among most Alawites, despite them being in many ways ‘favoured’; it massively thieved from them, while treating a generation of their young men as cannon fodder for these thieves. Yet the widespread alienation of much of the Alawite population – discussed below – by March can hardly be denied. There are numerous reports of sections of the Alawite population having been aware of the coup plans and not warning about them. According to another account, “some had prior knowledge of the preparations to target general security, and some hid the remnants and their weapons in their homes, while others participated in hiding weapons near the Ali al-Qadi School in Jableh.” According to ‘S’, a Christian from Baniyas, where the worst subsequent massacre of Alawites took place, in Qusour neighborhood early in the evening of the coup attempt, the Alawite population packed their bags and returned to their villages, one telling him “Close your shop and leave, everything will be settled soon” (though he says Baniyas was the only part of Tartous province where this happened). To be clear – the actions of some alienated Alawites in no way justifies the wholesale slaughter of the Alawite citizenry that took place next, but it is clear that such stories would have provided fuel to the murderous sectarian response.

The Syrian government’s security response – and the sectarian pogrom

Top: Photos of the first 100 security personnel massacred by the Assadists spread outrage around Syria; Bottom: Cover of the Syrian Network for Human Rights’ preliminary report into the massacres of Alawites.

When news spread of the slaughter of the security forces and civilians, along with that of an attempted comeback by the genocide-regime of Sednaya, demonstrations erupted around the country. While the government sent in many more of its new General Security forces (GSS) to confront the insurgents, the Ministry of Defence (MOD) also began to mobilise forces of the new army, which had only just been stitched together, made up of former rebel brigades and still lacking effective command and control; and in addition, thousands of armed citizens descended on the coast for the same reason, responding to unofficial calls for “general mobilisation.” At least some of these calls for mobilisation were made by sectarian preachers in certain mosques, preaching anti-Alawite hate. As the SNHR reports, “In these operations, local military factions, foreign Islamist groups nominally affiliated with the Ministry of Defense but not organizationally integrated with it, and local armed civilian groups provided support to government forces without being officially affiliated with any specific military formation.”

While their main target was obviously the Assadist killers, among the ranks of these thousands were perhaps hundreds who used the chaos to launch horrific sectarian attacks on defenceless Alawite citizens (often in rural areas), whether driven by thirst for irrational collective ‘revenge’ for the Assadist nightmare they had experienced, hateful jihadist ideology or simply looting and pillaging. While the violators included some security officers, overwhelmingly undisciplined military factions and armed civilian groups were responsible for the killing, as will be documented below; internal security (the GSS) were largely more disciplined and focused on fighting the insurgency. One very important aspect is that the slaughter of hundreds of security personnel stationed there, and then the need to fight the insurgency, severely limited their ability to protect Alawite citizens from the undisciplined sectarian elements theoretically on their side.

The SNHR reported that these “widespread and severe violations” included “extrajudicial killings, field executions, and systematic mass killings motivated by revenge and sectarianism. Additionally, civilians, including medical personnel, journalists, and humanitarian workers, were targeted. The violations also extended to attacks on public facilities and dozens of public and private properties, causing waves of forced displacement affecting hundreds of residents. Dozens of civilians and Internal Security personnel also went missing, significantly worsening the humanitarian and security situation in the affected areas.” Horrific reports included the killing of entire families, killing men in front of their families, the separation and killing of all the menfolk in an area.

Killers who went door to door regularly asked whether the residents were Alawite or Sunni, then proceeding to kill the menfolk if the response was Alawite, according to SNHR. Many such cases are documented in the Amnesty International report released in early April.

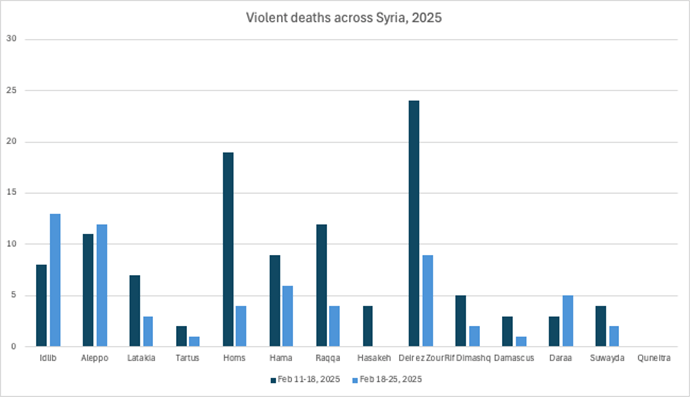

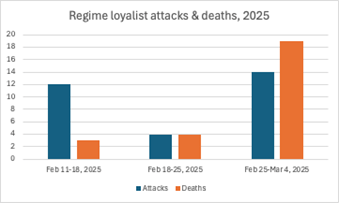

Five days passed before the respected SNHR released its preliminary full report; it took some time precisely because it aims to do a proper job, to at least attempt some initial sorting out of facts from the literal mountains of disinformation that spread around the world. The data released by SNHR in its March 11 report is horrendous enough, increasing in several updates. The following main data is from the latest April 16 update, while some extra information is from the more thorough April 9 update:

- 1662 unlawfully killed between March 6 and March 17 (most between March 6-10), of whom:

- At least 445 were killed by the insurgent Assadist forces, a figure which includes:

- – at least 214 members of security, police, and military forces

- – at least 231 civilians

- At least 1217 were killed by “armed forces participating in [government-led] military operations (including “military factions, armed local residents, both Syrian and foreign, General Security personnel”) during the extensive security and military campaign.” SNHR assessed that the “vast majority” were carried out by certain “military factions” that only recently joined the new Syrian army. More on this below.

- These victims were mostly civilians but some were “disarmed members of the [previous] regime remnants.”

- The latter group seems to refer to some who took part in the Assadist insurgency without uniforms, were disarmed in the fighting, and then field-executed. The SCM report noted the same thing, claiming the dead “included disarmed participants in the Assadist insurgency,” stressing this is still a war crime. SNHR reports that “It is extremely difficult to distinguish between civilians and disarmed Assad regime, as the latter were wearing civilian clothing.” However, according to the government’s investigative report, released in July, “some of the victims were former military personnel who had reconciled with the authorities,” which is even worse, because this means by then they were indisputably civilians. It notes that “the presence of Assad regime remnants among the dead cannot be ruled out,” but states “most of the killings occurred either outside combat zones or after the conclusion of military operations.”

- The fact that many Assadist officers were in civilian clothing, or that some Alawite armed civilians joined the insurgency, “emerg[ing] with personal weapons as soon as the attacks began,” is not controversial. According to local Tartous journalist Ram Asaad, the Syrian government is responsible for the outcome “because it confronted them [the insurgents] inside cities and it cannot distinguish between civilians and remnants,” but this is because “the regime remnants wear civilian clothes, and are spread among civilian neighbourhoods. There is no distance between them and civilians.”

- The killings included 60 children and 84 adult women (according to the April 9 update), 51 children and 63 women attributed to the pro-government forces, and 9 children and 21 women to the Assadist insurgents.

- The SNHR notes there were also an unspecified number of Assadist troops killed, estimated to also be in the hundreds, but that it “does not document the deaths of non-state armed group members during clashes, as the killing of these forces is not considered illegal.”

The caution taken by the SNHR in releasing its data is replicated by Amnesty International, which took almost a month to release a report, though Amnesty only interviewed 16 Syrians, all Alawites. Meanwhile, the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM) released an updated report on July 11 claiming 1,060 casualties among civilians and some disarmed Assadist insurgents (considerably lower than the SNHR update’s figures), along with 218 deaths of members of the General Security forces (slightly more than SNHR). The government’s Investigative Commission’s report, released in July, reported 1,426 mostly Alawite civilian deaths (while noting, like the SCM, that many Sunni civilians were killed in the initial Assadist attack), thus a higher figure than either SCM or SNHR, as well as the death of 238 security personnel. The UN Commission of Inquiry report, released in August, reported some 1,400 people, “predominantly civilians,” were killed, along with “hundreds of interim government forces.”

Meanwhile, while responsible bodies were taking time and care with their reportage, most of the world’s media impatiently reported the claims of an organisation called the ‘Syrian Observatory of Human Rights’ (SOHR), run by one Rami Abdulrahman, from a computer in Coventry, UK. The SOHR’s numbers of murdered Alawite civilians jumped from 134 to 340 to 745 to 973 to over 1000 all within about 24 hours (and then up to some 1700 within a few days). While the actual numbers were horrific enough, releasing “data” at such a rapid pace would make any cross-checking for accuracy impossible and does not do justice to the victims (by contrast, the well-respected SCM’s 1060 figure was a reduction of some 100 from its initial report “as documentation and verification continued, showing that some of the names were duplicate, and that some individuals were included as dead based on multiple sources, and it was later found that they were still alive”). Notably, the SOHR and Abdulrahman have long been considered either unreliable or suspect by Syrian activists, in particular for claiming at times that the number of Assad regime troops killed was higher than the numbers of civilians killed, a claim defying basic objective logic. We can leave further aside claims of “7000 Alawites and Christians” killed made by various propaganda quarters.

Alawite victims of sectarian killings also included well-known figures who have been involved in the movement against the Assad regime for years or decades.

Anti-Assad Alawites, Abdul Latif Ali, murdered, and Hanadi Zahlout, who lost her brothers to murder, by sectarian pogromists.

Opposition activist and former Syrian prisoner Abdul Latif Ali was executed outside his home along with his two sons in front of his wife and other female family members. According to a Syrian friend, “In 1970, he was among a small group of left-wing Alawites from Jableh who attempted, unsuccessfully, to organize protests against Hafez’s coup. Infiltrated by Hafez’s informants, he and his comrades were detained and viciously beaten before they even had the chance. He was ecstatic when the regime fell in December. In his last Facebook post, he urged young Alawite men not to fall for the trap being laid by henchmen of the former regime.” Here’s what his daughter had to say regarding false claims he was killed by the Assadist remnants.

Hanadi Zahlout, a prominent activist who took part in the uprising against the Assad regime in 2011, mourns her 3 brothers, “murdered in cold blood yesterday in Syria’s coastal region.” President al-Sharaa rang her to express his condolences. She thanked him and said she was putting her faith into the official investigation.

The lives of anti-Assad Alawite activists are not more important than those of innocent Alawite civilians slaughtered. But it does highlight the completely counterrevolutionary nature of sectarian crimes, and the stain of sectarianism in general.

These events were horrific for all involved, the terrorised Alawite civilians of course, but also the families of the new security officers and civilians slaughtered by the Assadist officers. However, Assadists can be expected to act like Assadists. It is impossible to overestimate the feelings of sheer terror, as well as betrayal, of Alawite civilians, hoping for something better with the fall of the regime that treated them as a mix of dirt and cannon fodder, now being subjected to such a terrifying pogrom by forces aligned with the government, however undisciplined and in open violation of government orders they may have been.

Disinformation overload

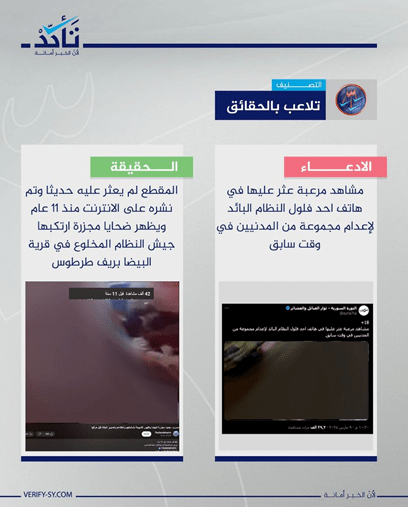

There have also been mountains of misinformation and absurd exaggeration. While none of this changes the reality of what did take place, it is important to understand the levels of nonsense floating around cyberspace. It is unwise to share any images or testimonies you are not absolutely certain are the real thing. Here is just as small handful of examples.

The first is explained in the tweet itself: an example of passing off crimes of the Assad regime as crimes committed now against Alawites. The creator of the original dishonest meme is the strange web-virus calling itself ‘Syrian Girl’, who spent 14 years actively supporting the genocidal crimes of the Assad regime, such as this one she now tries to credit to “Jolani’s gangs.” Similarly, as revealed by the excellent Verify Syria site, the second example is a “widely shared video, allegedly from a fallen regime member’s phone, claimed to show summary executions of civilians. The footage actually dates back to 2013 and documents a massacre committed by Assad’s forces in Tartous.”

Like here again, from 2012 (top photo above), and even Assad’s sarin massacre in Ghouta in 2013 is now claimed for the Syrian coast in 2025 (bottom photo)!

Another class of examples are those that claim crimes committed by Israel were actually occurring on the Syrian coast at the time. Verify Syria exposed this “widely shared video [which] claimed that Syrian aircraft bombed civilian homes with barrel bombs. In reality, the footage shows Israeli airstrikes on Qusaya, Lebanon, in December 2024.” Even crimes committed in India were passed off as crimes on the Syrian coast. The second photo above, showing a Syrian child named Dahab Munir Alou, and claiming her as a victim in the recent coastal violence, “has been circulated online multiple times over the years, with the earliest record dating back three years.” Still another class of misinformation images are countless cases claiming people have been killed who then turn up to demonstrate that are in fact alive. The video above on the bottom claimed that Dr. Kinanah Ali and her children had been killed. The doctor later appeared in this video, denying the news and confirming that she was alive.

There were also false claims about government policy. According to Verify, “claims that Syrian forces banned media from covering arrests and summary executions are based on a forged document. The alleged directive was altered from a February 14 order on military asset transfers.”

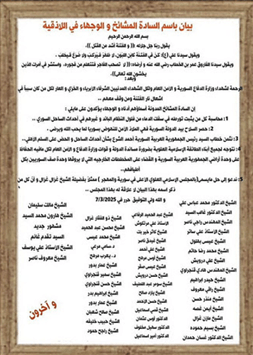

One specific aspect of disinformation was the assertion that Christians were also being slaughtered. The fact that these were lies does not make the actual slaughter of Alawites any better, of course, but the claims about Christians were aimed at western Islamophobic audiences. Among leading Trumpist circles, such claims, based on mountains of social media memes, were made by Elon Musk, Tucker Carlson, Vice-President Vance, and even Jim Risch, chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

The claim was not upheld in any of the human rights reports, and was denied in a statement issued by the Pastors of Christian Churches in Lattakia, who also advised in response to claims being spread on social media pages, “we kindly ask that you always rely on news issued through the official church pages exclusively, and we urge you not to be swayed by rumors, especially after the reassuring message we heard during the meeting we held this evening with a delegation from the leadership of the Syrian General Security Administration.” Syrian Bishop Hanna Jallouf, head of Syria’s Catholic Church in Aleppo, confirmed that “No Christians have been killed in Syria – claims to the contrary are false and misleading.”

Several Christians were killed in the chaos, one father of a priest in a carjacking by some people looting, one over a land dispute, and, ironically, two killed by Assadist gunmen shooting up cars with Idlib numberplates. Clearly, Christians were not specific targets in any of these cases.

Again, none of this means that horrendous killings did not occur. But misinformation does a disservice both to the real victims, by causing doubt about all claims, and to the actual victims in the other cases being misrepresented. The irresponsible spreading of lies by enemies of the Syrian people aims only to inflame the situation.

Syrian government reaction

Confronted with the Assadist insurgency and the slaughter it unleashed, the Syrian government sent in more security forces, but unofficial calls for a ‘general mobilisation’ spread around the country. This was partly responsible for the large-scale descent on the coast by factions and armed civilians from around the country that led to the chaos in which civilians were killed in large numbers. Latakia resident Alaa Awda claims that these calls for a general mobilization opened the way “indiscriminately for everyone to come to the coast, whoever they are, some of whom want to settle scores on a sectarian basis.”

However, already on March 7, the Military Operations Administration declared “the state does not need men to fight in its ranks or to declare a state of emergency in mosques,” and shortly afterwards, al-Sharaa called on “all forces that have joined the clash sites to fully obey the military and security leaders there, and to immediately evacuate the sites to control the violations that have occurred.”

In his first statements on Friday March 7, Sharaa condemned attacks on civilians and stated “everyone who attacks defenceless civilians and attacks people for the crimes of others will be held strictly accountable.” However, it was not immediately clear from this speech that forces fighting for the government side were already responsible for a large part of such attacks and of a most reprehensible form; and his primary attack was on the Assadist forces who had precipitated the disaster with their own massacres. While putting primary blame on the Assadists certainly had validity given their precipitation of the crisis, this statement arguably did not respond with the gravity required given how terrible the situation already was in relation to the slaughter being unleashed by elements of the pro-government side.

Sharaa stated “What distinguishes us from our enemy is our commitment to our principles. When we compromise our morals, we become our enemy on one level.” While this part of the statement is very good, it is still not clear from it that large numbers had already done precisely this, that they were precisely not “distinguishing themselves” from the Assadist enemy. He called on the security forces to “not allow anyone to overstep or exaggerate in their reaction” (to the Assadist insurgency), but it was unclear that overstepping was already going on on a large scale. He stressed it is their role to protect all the citizens of the coast, yet added, “from the gangs of the fallen regime.”

The interior ministry put the killings down to “individual violations” and pledged to stop them. “After remnants of the toppled regime assassinated a number of security personnel, popular unorganised masses headed to the coast, which led to a number of individual violations.” The source stressed that “these violations do not represent the Syrian people as a whole,” a welcome statement to be sure, but the violations were well beyond “individual” and had already become “mass” violations.

By March 8 the tune was changing. “We will hold accountable, firmly and without leniency, anyone who was involved in the bloodshed of civilians … or who overstepped the powers of the state,” al-Sharaa declared. That morning the government halted military operations, having largely defeated the Assadists, and shut all roads in order to remove gunmen not under the command of the Defense and Interior ministries, and began making arrests. By late in the day, “at least five different groups of gunmen had been captured.”

On March 10, Sharaa again upped the rhetoric level. Noting that that “many parties entered the Syrian coast and many violations occurred, it became an opportunity for revenge,” he said. “We fought to defend the oppressed, and we won’t accept that any blood be shed unjustly, or goes without punishment or accountability. Even among those closest to us, or the most distant from us, there is no difference in this matter. Violating people’s sanctity, violating their religion, violating their money, this is a red line in Syria.”

On March 9, the government announced the appointment of an “independent investigation and identification committee, to look into the atrocities committed against both civilians and government forces.” The investigation commission consists of seven people (including two Alawites), made up of five judges, a senior forensics officer and a human rights lawyer.

Its mandate includes “investigating the causes, circumstances and details of the incidents, examining human rights violations suffered by civilians and identifying the perpetrators, investigating attacks on public institutions, security forces and military personnel, and referring those found guilty of crimes and violations to the judiciary.”

The government also announced a High Commission for Civil Peace in the coastal region, tasked with “meeting with communities and listening to them, ensuring their security and safety.” On March 19, the commission held a meeting with senior Alawite notables in Latakia and agreed on a set of measures, including release of Alawite detainees and others currently under investigation, removing any restrictions on former regime soldiers currently holding settlement cards, limiting arrests to those believed to pose imminent security threats, removing government forces from residential buildings which they had occupied as new checkpoints, and establishing phone lines dedicated for receiving complaints.

In addition, according to journalist Haid Haid, local authorities in Latakia announced mourning ceremonies for all victims of the violence, both civilians and security forces. However, they also announced celebrations of the anniversary of the revolution in days soon after the carnage. In Latakia and Tartous, the feelings regarding anything resembling a celebration, even for those most associated with the revolution, would be very mixed in the circumstances to say the least.

I am not citing speeches by al-Sharaa or other government statements, or providing information about the accountability and civil peace mechanisms, in order to sow illusions. Whether these statements are reflected in real action and whether these mechanisms lead to real accountability remains to be seen and should be judged on that basis; that is virtually a life and death test for the revolution. On March 24, the investigative committee met with the UN Commission of Inquiry in Damascus, reportedly planning to coordinate their work on the issue; this certainly seems to be a positive, but again, results are what count.

However, it is important to distinguish the actions of undisciplined sections of security and armed forces from the security operation as a whole, which was unfortunately made necessary by the Assadist insurgency; and to understand that the massacre of Alawites was not a policy of an “al-Qaeda regime” as much anti-Syrian propaganda purports, even if we can be critical of government policy in relation to the events, and in relation to the Alawite question leading up to the events (to be discussed below), and since.

And the improvement in al-Sharaa’s statements, while perhaps simply reflecting the fast pace of events, may also reflect pressure from the outrage expressed by thousands of Syrian revolution activists with the massacres, which goes against all they have fought for the last fourteen years; the revolution is the people and their demands as long as they have not been crushed, the revolution is not the regime.

Arrests

Arrests of perpetrators began on March 8 and has continued. The following two photos are from the ‘Syria Weekly’ compilation of March 4-11.

The first photo below shows a fighter from a MOD formation being arrested by Military Police in Latakia on March 10, accused of committing crimes against civilians which he filmed on his phone; the second photo, another four men arrested on March 11, accused of committing violations “and “unlawful violent acts against civilians” in Latakia.

The Military Police also arrested these two MOD fighters below on March 10, after a video of them committing “bloody violations of civil rights in a coastal village went viral.” They were “transferred to the special military court.” Second image is video of the March 9 arrest of “Hussein Wassouf and his group” accused of committing crimes against civilians.

According to long-time and well-known Syrian journalist and activist Hadi Abdullah, “more than 50 elements from the Ministry of Defense have been dismissed and transferred to the investigation for suspicions of their involvement in violations and individual offenses, and a follow-up of those who appeared in videos of other violations is being carried out.”

[Following the release of the government’s investigative committee report in July, which alleged some 298 individuals were involved in these killings, the first 42 have reportedly been arrested].

Who was responsible for the civilian massacres?

Tens of thousands of people both from official security bodies and unofficial armed civilians initially descended on the coast in the chaos to fight the prospect of a return of the genocidal dictatorship and to avenge the initial slaughter unleashed by the Assadists; some 1217 Alawite civilians (or ‘disarmed troops’) were killed according to the SNHR. Such numbers indicate that the vast majority of pro-government combatants did indeed focus their fight on the Assadist insurgents and did not target civilians.

Unfortunately, while war in general brings out the worst in people, in a chaotic situation in which the new government has only just set up new security and military forces, and the whole system of command and control remains rudimentary, violations are even more likely to occur; and even more so in an atmosphere pumped with sectarianism by the genocidal Assad regime sectarian laboratory, with many out for murderous collective ‘revenge’.

While many people on all sides of the debate will not like me making the analogy, I believe these factors also describe what happened in the Gaza pocket in southern Israel on October 7. Likewise the Hamas leadership claims it only aimed at the occupation military bases but that violations took place against the orders. This is not the place to make judgements on this, I’m merely reporting the statements. Like on the Syrian coast, thousands crossed the Israel-Gaza demarcation line (including large numbers outside Hamas leadership control), and hundreds of Israeli and other civilians were killed. In both the October 7 and March 7-8 cases, if anything even close to the majority of fighters were out for civilian blood, we would have seen thousands upon thousands killed. But hundreds, or even mere dozens, of fighters (whether uniformed or otherwise) determined to kill can kill a lot of people.

So who committed most of the sectarian crimes? Violations were reported by elements of all forces involved: elements of the security forces, ‘factions’ of the MOD military forces, and armed civilian groups, but far more from the last two categories than from the first. First, it might just be useful to explain the difference between these groups and who they are:

- The “security forces” refers to the new General Security Service (GSS) set up by the new government under the Internal Affairs Ministry. According to very knowledgeable Syria watcher Gregory Waters, these forces “are generally speaking legacy HTS and Salvation Government formations, at least at the leadership level.” Both local police and GSS units “have roots in Idlib’s SSG political or police offices.” He assesses that this “has resulted in the Ministry of Interior appearing to have better command over its units, who in turn have an overall better track record of professionalism, than the country’s military units.” This assessment fits with the evidence below.

- The new Syrian Army, under the Ministry of Defence (MOD), formed from dozens of former rebel factions, including HTS itself, which were asked to dissolve in January. Most, but not all, did so. However, Waters assesses that “this was almost entirely a symbolic process,” and “by and large, most armed groups have not merged into the new ministry, let alone dissolved.” Moreover, the least integrated into the new structure are the military factions from the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA), which “retain their own independent revenue streams through both Turkish salaries and years of criminal activity in northern Syria and foreign deployments.” These SNA factions “are only nominally under the Ministry of Defense.” Once again, this fits with the evidence that certain SNA military factions were overwhelmingly responsible for large-scale crimes in the coast.

- Armed civilian groups – this category includes both local Sunni civilians, and civilian groups that initially poured in from outside the coast.

- Foreign jihadi groups, previously associated with HTS but now integrated into neither the GSS nor the Army can be included as a special category.

The General Security forces (GSS): Reportedly the most ‘disciplined’ and ‘professional’

According to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights many of the cases documented were of “summary executions carried out on a sectarian basis reportedly by unidentified armed individuals, members of armed groups allegedly supporting the caretaker authorities’ security forces, and by elements associated with the former government [ie, Assad regime]”. Thus the new security forces (GSS) are not specifically noted. Similarly, the SCM report only notes “armed formations affiliated with or loyal to the Transitional Government’s Ministry of Defense, alongside foreign fighters, were involved in carrying out the violations,” while the Investigative Committee’s report “identified individuals and groups linked to certain military groups and factions from among the participating forces.” The SNHR report does include violations by “General Security personnel” along with “military factions [and] armed local residents, both Syrian and foreign,” but assesses that the “vast majority” were carried out by certain of these “military factions” that only recently joined the new Syrian army, rather than by wayward GSS. The UN Commission of Inquiry report likewise included general security alongside military factions, but stressed that “many interim government forces elements neither engaged in nor condoned the actions of those groups … to the contrary, it has documented their active efforts to evacuate, or protect certain populations and individuals” (p. 17-18).

Long time Syrian writer, activist and former political prisoner Yassin al-Haj Saleh basically concurs with these assessments:

“My impression, which needs verification, is that there are three subgroups within the armed formations that poured into the coastal areas after the bloody events of March 6.

“The first consists of organized forces from the General Security and the new army.

“The second includes sectarian Sunni Syrian groups like Amshat and Hamzat.

“The third consists of jihadist groups, including foreign fighters.”

Regarding the first group, the General Security (GSS) forces, Saleh writes that it appears that “in some cases, [they] exercised excessive repressive violence and captured Alawite civilians. … However,” consistent with the previous two assessments, “it was also the most disciplined, limiting further casualties in some instances, and it suffered significant losses in confrontations with armed Assad loyalists.”

It therefore appears clear that, on the whole, the new General Security forces should be distinguished from certain military “factions” of the army, armed civilian groups and jihadis. That does not mean there were no cases of General Security taking part in violations; there were. But let’s look at some evidence that backs up this general pattern.

The SNHR report claims there were “instances of direct clashes … between armed groups supporting the government’s security forces on one side and elements of the Internal Security forces who attempted to prevent indiscriminate killings on the other. In some cases, these clashes escalated into armed confrontations between the two sides” (p. 13).

In Homs, the government’s security forces formed cordons around areas to protect the Alawite citizens from armed gangs. The effectiveness of this was confirmed by an Alawite woman interviewed on Gregory Waters’ excellent Syria Revisited blog: “We were very scared, I didn’t go to work, we thought our turn would be next and the massacre would reach Homs soon … The General Security forces played a huge role in protecting the Alawite neighborhoods. They gathered more forces and forbade any armed groups to enter our neighborhoods, I may be able to say that without their protection, Alawite Homs could have faced the same destiny the coast had been facing.”

This was perhaps easier as the Assadist insurgency took place in Tartous and Latakia, so the security forces were able to be highly successful in less affected Homs; only three deaths were recorded in Homs over these days. This figure is surprisingly low, because Homs – with its mixed population – was much more the epicentre of sectarian conflict throughout the war, but also in the earlier low-lying post-Assad conflict, overlapping with random killings in a security vacuum, in the late December-January period, Homs had been far more impacted than the coast itself and has continued to be in its aftermath.

Public Security Forces in Homs forming a human barrier in a majority Alawite neighborhood.

In this report from the town of Qadmus – an Ismaili town surrounded by Alawite villages – the interviewee reports no problems with the police or security forces, but some of the “factions” – meaning military factions – did commit crimes in the countryside (as did the Assadists).

Similarly, Latakia resident Alaa Awda recalled that “the clearing operations on the coast were carried out in several stages. When general security entered for the first time, they were professional.” Then, when other forces entered — factions affiliated with the Ministry of Defense — “they were harsher, with executions, assaults and robberies.” Or this Alawite woman interviewed by the Syria Revisited blog, who claims more generally that “security men are more professional in solving problems peacefully and they try to keep all things under control,” whereas “military members act more quickly and direct … they make a scene every time they do something … [they are] somehow more harsh and cold.”

The SCM report cites a case of killings in the village of Aziziyah in western Hama province carried out by “armed men … from neighboring Sunni-majority villages in the al-Ghab plain.” The witness did not know whether the men belonged to any government military formation, but he stated that “General Security personnel treated civilians respectfully and were not implicated in any violations.”

Researcher Gregory Waters similarly reports that “while some GSS members participated in extrajudicial executions during the March violence on the coast, Alawites and Ismailis have consistently described GSS behavior as much better than that of the [military] factions in Hama, Latakia, and Tartous … This is a trend that the author has found across most minority regions, and seems to reflect a generally higher degree of professionalism on the part of Ministry of Interior units when compared to the various military factions.”

Even this report by an anti-Assad Alawite coastal resident, which is completely gut-wrenching in its description of the mass murder and the terror of the Alawite citizens, and which puts indirect blame on the government itself, nevertheless also reports on an incident in which security forces directly aided Alawite citizens escaping from danger, and speaks of the security forces “trained in Idlib” who were “known for their professionalism and respectful conduct toward the people of the Syrian coast.”

On the other hand, Alawite anti-Assad civilian ‘J’, who reports “all my friends and loved ones are dead now,” claims that some of the security forces in Baniyas were involved in killing and looting, but after a point “the General Security men began to calm things down and stop the looting and fighting.” Clearly as noted above, they were not all innocent, but even this negative report paints them in a different light to the military “factions” and armed civilians that he claims carried out most of the killing (see below).

On the other hand, we sometimes hear that the security forces, while not generally the perpetrators, “did not protect civilians” from them (despite numerous other reports, as cited above, when they did). It is unclear if this means that security forces present did nothing in the face of violence from other factions, or that they were not present to protect. In the latter case, first, the massacre of hundreds of security personnel who had been stationed in the region initially hugely weakened their capacity to protect anyone; secondly, those remaining, and those rushed in from the outside, had as their first priority crushing the Assadist revolt. It appears that many of the massacres took place in vulnerable rural areas away from where the main action was. Therefore, this is difficult to assess.

For example, the Amnesty report notes that “according to residents” in one area of their study [note: Amnesty only interviewed 16 civilians in total], “the authorities did not intervene to end the killings, nor did they provide residents with safe routes to flee the armed men.” But it then goes on, “Three others said the only way for them to flee was when, eventually, they were able to secure car rides from Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham [HTS],a former armed group integrated into the government armed forces.” As noted above, the GSS (security forces) are virtually a proxy for armed HTS cadre. How ironic that Alawites are aided in fleeing from violent factions by forces of what was once the most ideologically anti-Alawite faction.

Countless other examples of security forces acting professionally in contrast to either ‘factions’ or armed civilian groups acting murderously can be cited. The official Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA) also claimed that security forces returned more than 200 vehicles stolen by those they claimed “took advantage of the instability” on the coast.” On the other hand, the Reuters report does document cases where members of the GSS were directly involved in massacres, so this should not be read to mean they were uniformly innocent.

Military ‘factions’, ‘foreign jihadis’, ‘Amshat and Hamzat’ – Heavily reported as responsible for massacres

So, who committed most violations and what were the causes?

Yasin al-Haj Saleh claims that the other two groups [ie, military factions “like Amshat and Hamzat,” and “jihadist groups, including foreign fighters”] “engaged in genocidal violence—killing Alawites solely because they were Alawites. One acted out of a malevolent ideological conviction, while the other was driven by a mix of revenge, warlordism, and looting.”

It is difficult to separate motivations of groups, but my understanding is that Saleh means the third group, the actual jihadists – which includes foreign jihadi factions from the Caucasus or central Asia who were around HTS and have remained in the country since liberation – were those who acted out of “malevolent ideological conviction,” ie pure sectarian hatred of Alawites. While the HTS leadership has moved away from this stance, there remain strong elements of its base who hold these views; and given that foreign jihadi fighters entered Syria for the purpose of “waging jihad,” many may hold firmer to such malevolent ideas than many locals who have to relate to the Syrian society around them. Foreign jihadi fighters were reported in relation to violations in both the SNHR report and the SCM report (p. 19, 31). However, “foreigners” cannot be conveniently singled out for most blame.

Indeed anti-Alawite sectarian hate speech was widely reported to have emanated from various mosques. For example at this Aleppo mosque, a preacher tells hundreds of Syrians that “the land of the Levant cannot, cannot be anything but pure … the Levant was Sunni and will remain Sunni … the Sunnis must now unite and must know who their enemies are … we yearn for martyrdom, we yearn for battles, we yearn for killing.” Many examples of such hate speech spread not only by preachers but other social media influencers are collected in this report. Though it is unclear, it is possible that many of these hate preachers and influencers are associated with unreconstructed sectarian elements of the former HTS base. On the other hand, some preaching mobilisation warned against committing “transgressions.”

I believe Saleh is referring to the second group, “Amshat and Hamzat” – two military factions from the Turkish-backed ‘Syrian National Army’ (SNA) – as those driven by “a mix of revenge, warlordism, and looting.” “Amshat” refers to the Sultan Suleiman Shah Brigade of the SNA, named after its commander Mohammed al-Jassem‘s nom de guerre Abu Amshat. “Hamzat” refers to the al-Hamza Brigade of the SNA. Both brigades have a long history of war crimes and other violations, including abduction, extortion, torture, rape and murder, especially in Afrin, where al-Hamza ran an illegal women’s detention facility. Both militia are under sanctions by the US Treasury Department for violations in Afrin and elsewhere.

It is certainly true that these two SNA factions have been widely reported by countless Syrian sources to have been responsible for most of the sectarian killing. The SCM report specifically describes a number of cases, and the groups identified included Amshat and Hamzat, along with three other notorious SNA brigades, Sultan Murad, Ahrar al-Sharqiya and Jaysh al-Islam (pp. 18-19, 31), as well as a military brigade (Division 400) which was not SNA, but previously belonging to HTS. Likewise, the massive Syrian Archive report, based on open-source information, which documents the presence of every armed group on the coast, gives specific information about killings carried out by Amshat (p. 7-8), Ahrar al-Sharqiya (p. 9), an independent Qalamoun brigade, the ‘Lightning Battalions of Islam,’ which deployed “in coordination with the SNA Muntasir Billah Brigade” (p. 17), and members of the Al-Boushaaban tribe (p. 18). The UN Commission of Inquiry report also specifically documents the involvement of Amshat, Hamzat and several other brigades in various crimes.

“Warlordism and looting,” along with wanton murder, has indeed been the modus operandi of the worst SNA factions for many years, since their role in the Turkish invasion of Kurdish Afrin in 2018, so this is not surprising. These factions, like the rest of the SNA, are officially part of the new Syrian army (as opposed to the General Security), but as noted, this new “army” has only just been formed by cobbling together dozens of military factions from the old opposition throughout Syria, and the SNA brigades have only partially integrated; indeed, there is little evidence that any effective system of control and command has yet been established.

Ideologically, the SNA is an oddball collection which includes former secular FSA brigades and Islamist brigades alike, while the Suleiman Shah Brigade and another SNA brigade, the Sultan Murad Brigade, are Turkmen-based brigades, influenced by Turkish-nationalism. HTS’s origins in Jabhat al-Nusra mean it was more steeped in anti-Alawite sectarianism than any group in the SNA hodge-podge; the SNA in contrast is more likely to have specifically anti-Kurdish biases due to Turkey’s sponsorship. Therefore, it may seem odd that the worst violations appear to have been committed by SNA brigades like Amshat and Hamzat; and likewise the Turkish-nationalist Sultan Murad Brigade of the SNA was also implicated in attacks on Alawites in January, and again in the March massacres. What specific issue would these SNA brigades have with Alawites?

Most likely, it has little to do with Alawites as such, but rather what the SNA represents: a long-term degeneration of a number of groups, whereby Assadist repression forced them more and more under Turkey’s wing; being sponsored and paid by a state to do its bidding – whether anti-Kurdish offensives in Syria or participation in Turkey’s foreign ventures in Libya or Azerbaijan – meant the needs of their local base of support became less important. It is in this context that open criminality became the norm for some SNA groups, and indeed, a major additional form of financing.

That said, the SNA cannot be reduced to its famed criminality; the north near the Turkish border is where hundreds of thousands, indeed millions, from all over Syria took refuge from the Assadist slaughterhouse, fleeing their destroyed homes and towns and cities, and “disappearances” and torture chambers, and many would have had no other options but to sign up to a Turkish-backed militia. Needless to say, irrational collective ‘revenge’ would also likely be a major motivating factor among many of these dispossessed people now in SNA uniform. Finally, some of the SNA brigades, for example Jaysh al-Islam, whose cadres were displaced to the north after being expelled from Ghouta in the south, was always as fundamentally Sunni sectarian, anti-Alawite as HTS, if not more so; and this was alos the case for certain hard-Islamist northern brigades which were incorporated into the SNA, even if that was not a defining SNA charatceristic.

Getting back to the looting and wanton criminality, not all of it can be attributed to these SNA factions, but it is important to note that these motivations were important additions to jihadi ideology or lust for collective ‘revenge’. For example, this account from Jableh from Syria Direct by a Sunni resident al-Abdullah claims that when pro-government armed “factions” arrived in his town after the townspeople had driven back the Assadists, “the city suffered billions [of Syrian pounds] in material losses due to attacks on shops and homes. … [he denounced] “the poor morals of some of the groups, which engaged in vandalism and looting, with no differentiation between Sunnis and Alawites.” His family’s shop was “robbed and vandalized by some of the groups” that ostensibly came to “support” them. Another local, Omran, likewise claimed that “Some of the factions that entered Jableh committed widespread violations, including killings and theft against Sunnis and Alawites.”

The Alawite citizen ‘J’ (cited in the Syria Revisited blog) claims that his house was raided by five separate groups on March 7, of which the first group, a military faction from Hama, “were the worst and most violent and did most of the killings. They also stole gold, phones, cars, anything really.” The other four raids were either by other “factions” or by foreign jihadis, but none were as violent as the first; the next day the region was attacked by armed civilians from the countryside who were once again worse (see below).

HTS, in contrast to the SNA and perhaps some other unruly military factions, had been forced to deal with the Syrian reality where it ruled, and over time it adapted and became somewhat more pragmatic, despite its politically repressive rule and the ongoing existence of hard-line elements within its base.

For example, after taking over the Kurdish region of Afrin in 2022 from the SNA, HTS declared that it “confirms that the Arab and Kurdish people are the subject of our attention and appreciation, and we warn them against listening to the factional interests… We specifically mention the Kurdish brothers; they are the people of those areas and it is our duty to protect them and provide services to them.” In March 2023, HTS confronted the SNA after five Kurdish civilians were killed by members of a Turkish-backed faction during a Nowruz celebration in Jenderes. Jolani met with the Kurdish residents and HTS forces deployed in the town and seized control of headquarters of the military police and the SNA’s Eastern Army, which was accused of the killings.

Of course, Kurds are Sunni; Islamist groups like HTS include Kurds, and tend to be less ideologically Arab nationalist, while being more Sunni sectarian. Yet HTS also moved partially against its own sectarian background in Idlib in recent years, as I have documented here. Of course, these changes do not mean former HTS cadre do not commit violations; no doubt many do (as noted regarding Division 400), and changes at the top do not necessarily alter the long-entrenched sectarianism of sections of the base. However, this does help explain the widespread reports of several SNA factions bearing primary responsibility for the carnage, and of former HTS-led security forces being overall more professional.

However, some military brigades acted with integrity

All that said, the Syrian Archive report documents the presence of some 25 divisions of the new Syrian army (including from former SNA, NLF, HTS and new divisions), plus various independent militia and tribal fighters, on the coast at the time, yet the number of militia or military divisions specifically named in any of the key reports (SNHR, SCM, Syrian Archive, UN Commission of Inquiry, even the somewhat confused Reuters report) as committing violations and killings does not exceed the half dozen or so mentioned above. This is important, as the fact that most violations were carried out by wayward military factions does not indicate that the entire Syrian army acted as a genocidal gang during the events. It should be pointed out that the Syrian Archive report documents several cases where military brigades protected Alawite civilians from sectarian thugs and thus deserve an honourable mention:

First, referring to Faylaq al-Sham, a member of the mostly FSA National Liberation Front (NLF), the report states “On March 9, a civilian from the Jableh countryside posted several times on Facebook begging people to send the General Security to his house, and later wrote “Faylaq al-Sham, I will bear your debt until death. Thank God, members of Faylaq al-Sham saved us from the house before the arrival of undisciplined individuals intent on killing” (p. 11).

Notably, Faylaq was mentioned in another region, Bahluliyah in Latakia, by researcher Gregory Waters:

“According to one local I spoke with, the Faylaq commanders were respectful and professional as they searched the town. When they left, the commander gave everyone his phone number and said to call him if there were any issues. Later that day, another faction arrived – the witness does not know their name – and began looting homes and killing civilians. The man called the Faylaq commander, who returned and expelled the faction from the town. Faylaq al-Sham has remained in the Bahluliyah and Haffeh regions since March where it has a widely positive reputation.”

Getting back to the Syrian Archive report, it also discusses the well-established FSA brigade from northern Hama and Idlib, Jaish al-Izza (now the 74th Division). It was an independent brigade which was never in the SNA; the report claims it as a member of the NLF. Its commander issued instructions to its checkpoints and personnel in north and west Hama: “Random entry into villages and towns without coordination with the division’s leadership is prohibited. Any vehicle not bearing proof of ownership will be confiscated. Entry into neighborhoods and villages with sectarian diversity will not be permitted for the purpose of revenge. Residents of villages and cities are safe as long as they adhere to the instructions and decisions of the Ministry of Defense. Strict orders will be issued to deal with anyone who violates these instructions.” (p. 11-12)

The third group mentioned was the NLF brigade 77th Coastal Division, consisting of fighters originally from the FSA-held southern town of Zabadani, who were expelled to the north in 2016 following prolonged Assadist starvation siege; they were present in the Bahluliyah district of Latakia. According to a report of a villager, “factions [ie, military factions] in the villages of Al-Bahluliya, Da’tour Al-Bahluliya area, were burning houses and killing,” so he contacted 7th Division commander Abu Ahmed. Several villagers were killed by the “factions” and then in half an hour, “Abu Ahmed arrived with members of the 77th Brigade at the Al-Bahluliya junction. The faction said, “We will comb the village.” After some back and forth, the faction left, and Mr. Abu Ahmad and the elements of Brigade 77 spared “the village” from something that would have had undesirable outcome. Now Mr. Abu Ahmed has taken over the area for us. Welcome, may God bless you. Many thanks to the members of the 77th Brigade” (p. 14).

Armed civilians and “revenge” killing

But if unreconstructed sectarianism explained some crimes, and opportunistic wanton criminality others, what of the motivation for ‘revenge’? Lust for revenge by people whose families, friends and communities were slaughtered by the Assad regime, taking out their ‘revenge’ against innocent civilians, was clearly one of the factors here. Stating this is not to justify it. It is merely stating the reality that this is common in conflicts throughout the world. Most people involved in such battles may understand that the ordinary people on “the other side” are not at fault, and to kill ordinary citizens in “collective revenge” is to act no differently to one’s oppressors. However, not every severely damaged individual, who has known nothing but war, killing, atrocities and personal tragedy since their childhood “knows” this. From the atrocities on October 7, to brutal attacks on Kosovar Serbs by returning Albanian refugees driven from their country by Milosevic’s genocidal war, to countless anti-colonial violations and massacres around the world, so-called “revenge” takes place, especially in situations of security vacuum like in Syria where the old regime’s army and police collapsed and new ones take time to build.

The element of “revenge” may have been the most prominent among the undisciplined groups of “armed civilians” who were theoretically on the pro-government side but not under anyone’s command; yet putting on a uniform, whether security or military, does not always prevent these people, especially severely damaged young men, from acting differently. As such, this may have also been a motivation of many violators from other categories, whether General Security or military factions, especially SNA members as noted above.

We have some very direct examples of such collective revenge being taken out against an Alawite village, not by security forces or military factions or even armed civilians coming in from afar, but by local civilians from a neighbouring Sunni village who had been horribly mistreated by Assadist elements of that village under the previous regime; and security forces reportedly attempted to stop their carnage. This was reported in The Guardian:

“In Arza, local people say they know who their killers were. Three survivors accused the residents of Khattab, a nearby Sunni village, of being behind Friday’s massacre. Abu Jaber, a religious notable in Khattab and a former opposition fighter who had returned to the village, described how he and others entered homes, and forced men on to the town’s roundabout, with the purpose of displacing them from the village. “But then people who had their families killed [by the regime] came, and they opened fire,” he said.

“A survivor of the attack described how the killers left the bodies on the roundabout and began to loot houses, killing any men they saw while they pillaged. They said members of the Syrian general security tried to protect town residents, but were quickly overwhelmed.

“They came in the town chanting that they wanted 500,000 Alawites for the people they lost. They came into my house and took my brother and killed him in cold blood,” said a woman who was retrieving her belongings from her looted home, breaking down in tears.

“While Abu Jaber denied personally killing anyone, he said the people of Arza deserved their fate. He claimed that during the civil war the town’s residents had extorted and abused the residents of Khattab, and so the killings last Friday were merely people “claiming their rights”. He recalled a time when a regime official from Arza had bludgeoned a Khattab resident to death with a stone – and claimed the whole of Arza had celebrated after the killing. “What would you imagine that the villages that live around Arza, which committed these acts, what should they do? You think we should give them flowers?” he said.”

“Survivors of the Arza massacre admitted that select regime officials from the town did kill residents of Khattab,but said those officials had fled after the fall of Assad, and those left in the town had nothing at all to do with the previous abuses.”

Video of the attack on Arza show the attackers to be either ordinary villagers and/or criminal elements rather than security forces.

Similarly, the Alawite ‘J’ cited above claims that armed Sunni civilians were responsible for around 40% of the murders” in Baniyas. Importantly, both ‘J’ and Christian interviewee ‘S’ made a distinction between Sunni civilians in the town, who knew their Alawite neighbours and did a great deal to protect them, whereas “most of the local Sunnis who engaged in the murders were from the countryside,” notably, they were “from the areas the regime massacred in 2012 and 2013,” referring to the gigantic Baniyas massacre of that time (see below) – clearly another example of collective ‘revenge’.

On a smaller scale, an incident reported by Amnesty in its report tells of armed men raiding a home and killing the husband of a ‘Samira’, who said one of the men “blamed the death of his brother on the Alawite community.” When she protested that they had nothing to do with the former regime’s killings, he said “they would show him how Alawites had killed Sunnis.”

Such murders are clearly unjustified and appalling. However, these incidents raise the issue of where this came from – and therefore how this cycle can end.

Assad regime slaughterhouse: Incubator of sectarian mayhem

The Assadist slaughterhouse was the laboratory of sectarianism par excellence. This does not mean it was a religiously Alawite regime – it wasn’t, its ideology is better described as secular fascist – or that most ordinary Alawites benefited – they mostly remained poor and were torn apart by losing so many sons as cannon fodder for the regime. Rather, the Alawi-dominated regime weaponed sectarianism as a means of waging its counterrevolutionary war.

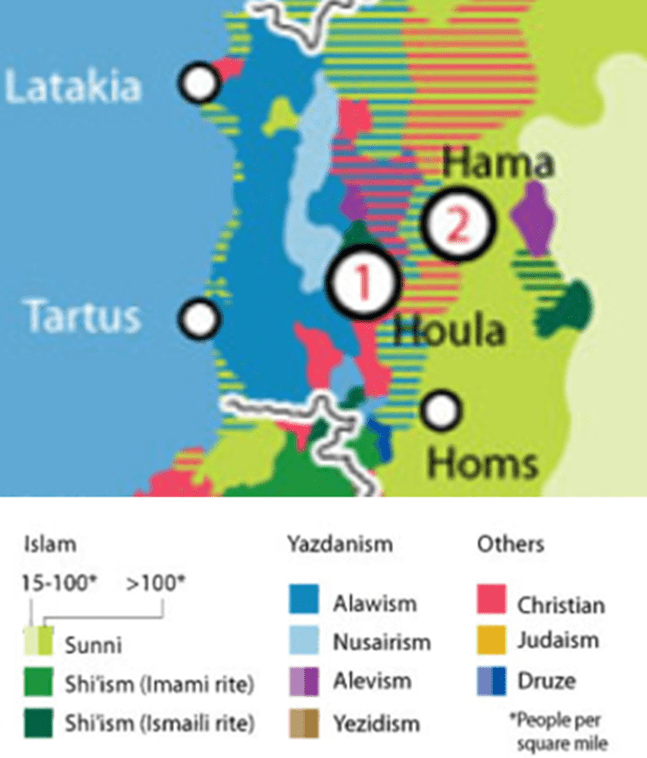

The regime itself was heavily dominated by the 10 percent Alawite minority, as this chart shows, though that was not ideological, but rather due to the nepotistic regime being dominated by the Assad family – who happen to be Alawite – and extended family, friends and connections, who lived like kings while the Alawite masses lived in poverty.

Most of the organs of state were also dominated by Alawites; as Syria expert Fabrice Balanche explains, noting that the initial uprising in 2011 aimed “to get rid of Assad, the state bureaucracy, the Baath Party, the intelligence services, and the general staff of the Syrian Arab Army,” this very fact could not help but tap an existing sectarian dynamic inherent in the Baathist set-up, because “all of these bodies are packed with Alawites, over 90 percent of whom work for the state.” If this figure is even roughly true, then, while certainly “working” for the state does not necessarily convey any kind of upper or even middle class status, it did put the average Alawite in a relatively privileged position compared to the average Sunni, placing two strategic tasks of the revolution – destroying the totalitarian state apparatus, and overcoming the sectarian divides – partially at odds with each other.

Above all, Alawite elements were absolutely dominant within the military and security apparatus of the regime — including head of the Republican Guard, chief of staff of the armed forces, head of military intelligence, head of the air force intelligence, director of the National Security Bureau, head of presidential security. According to Stratfor, quoted by Gilbert Achcar, “Some 80 percent of officers in the army are also believed to be Alawites. The military’s most elite division, the Republican Guard, led by the president’s younger brother Maher al Assad, is an all-Alawite force. Syria’s ground forces are organized in three corps (consisting of combined artillery, armor and mechanized infantry units). Two corps are led by Alawites.” Achcar continues: “Even though most of Syria’s air force pilots are Sunnis, most ground support crews are Alawites who control logistics, telecommunications and maintenance, thereby preventing potential Sunni air force dissenters from acting unilaterally. Syria’s air force intelligence, dominated by Alawites, is one of the strongest intelligence agencies within the security apparatus and has a core function of ensuring that Sunni pilots do not rebel against the regime.”

So when a regime that has ruled for decades, that is overwhelmingly Alawi-dominated, launches unlimited war against its population who rise up for democratic rights, and the majority of the rising population (though by no means all of it) just happen to be Sunni, then Alawite domination of the military-security apparatus waging this war becomes a fundamental aspect fuelling sectarianism. The towns and cities, or districts of cities, targeted for total demolition by this Alawi-led military were Sunni. As Syria expert Thomas Pierret explains:

“The problem is that many people do not even recognize the sectarian character of these atrocities, claiming that repression targets opponents from all sects, including Alawites. In fact ordinary repression does target opponents from all sects, but collective punishments (large-scale massacres, destruction of entire cities) are reserved for Sunnis.”