Bashar Assad, “nationalist” leader, held afloat by the intervention of both imperial superpowers and the rest of the world, hereditary ruler of a country now occupied by 36 foreign military bases, image from Radio Free Syria https://www.facebook.com/RadioFreeSyria/photos/a.382885705129976.91927.363889943696219/1477942602290942/?type=3&theater

By Michael Karadjis

The deepening American intervention in Syria under the administration of president Donald Trump has been both far bloodier than that under Barack Obama, and also more openly on the side of the regime of Bashar Assad, as has been clarified by a number of recent official statements and changes.

Emphatic pro-Assad orientation of Trump regime

First was the recent declaration by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson that the only fight in Syria is with ISIS, that the US and Russia must work together on Syria, that Assad’s future is Russia’s issue and that the US is largely agnostic about “whether Assad goes or stays.” Tillerson also made one of the clearest statements to date that the US sees all forces fighting the Islamic State (ISIS/Daesh) as essentially allies and that it has no fight with Assad:

“Actors in Syria must remember that our fight is with ISIS. We call upon all parties, including the Syrian government and its allies, Syrian opposition forces, and Coalition forces carrying out the battle to defeat ISIS, to avoid conflict with one another and adhere to agreed geographical boundaries for military de-confliction and protocols for de-escalation.”

This was followed by Trump’s official ending of the long-dormant CIA program to arm and train some “vetted” anti-Assad rebels. In reality, this effort was only ever aimed at co-opting and taming the rebels anyway. The aims of the concurrent Pentagon program were more explicit: it would only arm and train rebels who agreed to drop the fight against Assad and only fight ISIS or Jabhat al-Nusra, and therefore it failed, since few rebels would agree to such conditions; as was quipped, it aimed to support only those rebels who do not rebel. While the CIA program, in contrast, is normally seen as more supportive of actual anti-Assad efforts, in reality it mainly differed in style; by initially supporting viable Free Syrian Army (FSA) brigades, once such groups were entrapped by an arms pipeline, the CIA was in a position to then pressure them to stop fighting Assad, thereby enlisting real forces for the US “war on terror” against ISIS and Nusra. Yet even the anti-Assad façade was too much for Trump: he considered it “dangerous and wasteful.”

Even worse, Trump also ended US “stabilisation” funding for civil society in regions outside Assad regime control. Trump declared “the United States has ended the ridiculous 230 Million Dollar yearly development payment to Syria,” referring to the Obama-era funding, which went to a vast array of local governance and civil society organisations which kept society running in the absence of the regime. To be clear: the Trump regime put an end to all US funding, no matter how minimal, to both the civil and military sides of the revolution.

Further, the nature of any US aid to Syrian rebels has now been clarified: to be successfully “vetted” as a condition to receive aid is now officially synonymous with not fighting Assad. US Central Command spokesman Major Josh Jacques explained: “vetted Syrian opposition groups all swear an oath to fight only ISIS.” This command was recently reinforced in the southeast desert, where the US has been arming and training two “vetted” brigades for the war against ISIS. This led to one of the brigades, Shohada al-Qaryatayn, cutting off its relationship with the US-led Coalition due to “pressure from the US-led coalition to stop the fighting against the Syrian Arab Army (SAA)” in rural Suweida, Damascus and Homs. Another Coalition spokesman, US Army Col. Ryan Dillon, noted that Shohada Al Quartyan wanted “to pursue other objectives,” and that not only would the Coalition cease support, but would also retrieve “the equipment we provided them to fight ISIS.” Indeed, if they did not return the weaponry the US has warned that it will bomb them

It is notable that this US trajectory has continued and deepened even as conflict between the US and Russia in the global arena has sharpened elsewhere. As the US Congress and Senate voted in late July, against Trump’s wishes, for new sanctions on Russia (for its alleged meddling in the 2016 US presidential election), and Russia retaliated with the expulsion of 755 of the 1,210 US diplomatic staff in the country, both sides made clear this would not affect cooperation in Syria. Putin stressed that the US-Russian brokered southern “de-escalation zone” had seen “concrete results” and that such coordination would continue. Meanwhile, a “new” US strategy was in the same week presented to the House and the Senate by Defence Secretary James Mattis, State Secretary Tillerson and Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Joseph F. Dunford Jr., conceding Assad’s control of Syria west of the Euphrates River and most of centre and south. Discussing “a proposal that we’re working on with the Russians right now,” Dunford (who has sometimes been referred to as a traditional military “hawk”), noted “my sense is that the Russians are as enthusiastic as we are to ensure that we can continue to take the campaign to ISIS.”This has now reached the point where US personnel are “bragging” about their cooperation with Moscow. “The Russians have been nothing but professional, cordial and disciplined,” according to Lt. Gen. Stephen Townsend, Iraq-based commander of the US-led anti-ISIS coalition.

This trajectory is consistent with Trump’s stated policy in the lead-up to his 2016 election as US president. Trump promised to work with Putin’s Russia in Syria, to an even greater degree than Obama and Kerry had, asserting the US should be on the same side as Russia and Assad in “fighting ISIS”, and said the US would cut off any meagre “support” still going to the anti-Assad opposition. These policies in fact represented more continuity than change, but did point to the more emphatic counterrevolutionary policy that has come to fruition.

Bombs on Assad – a change in direction?

However, within a number of months of Trump’s election, some events began to cast doubt on this trajectory. Above all, in contrast to the complete absence of any military clash between the US and Assad in the Obama years, the first half-year of Trump saw one regime airbase bombed, one regime warplane downed, and three minor hits on pro-Assad Iranian-led Iraqi militia in the southeast desert.

Various reasons were put forward for these clashes, and the apparent contradiction between this military activity and Trump’s stated goals, which some believed were heralds of an almost inevitable US drift into conflict with either Assad, Russia or Iran, if not all three, despite Trump’s predilections. Of these reasons, three stand out.

First, from the outset, many observers said that while Trump and some of his leading officials may be pro-Putin for various reasons, others were traditional Republican “hawks”, who were either very anti-Russia or anti-Iran and aimed to “re-assert” US strength against these traditional rivals. Either they would undermine Trump’s policy, or Trump himself would be won over to their views, given his own American nationalism and militarism.

Second, many point to the glaring contradiction between Trump’s pro-Putin, and essentially pro-Assad, position on the one hand, and his rabid anti-Iranian rhetoric on the other. Since Iran is just as crucial a backer of Assad as is Russia, unless he could get quick results trying to divide Russia and Iran on Syria, Trump would stumble into conflict with Assad via conflict with Iran.

Finally, from a different angle, many assert that the common desire of both global and regional powers to avoid the collapse of the Assad regime via an outright revolutionary victory was the main obstacle all along to these rivalries coming out into the open. Now that Assad has largely turned the tables on the armed opposition, with the revolutionary uprising as a whole subsiding, the only thing holding the various global and regional powers back from openly fighting each other has now been removed. Therefore, traditional rivalry between the various imperialist and regional powers will re-assert itself.

As an extension of this, we also see all of these rival powers, in continually changing “blocs,” involved as “allied rivals” in the mopping up operation against the Islamic State in eastern Syria, so when that is over, there will be even more of the corpse of Syria to fight over.

While all three explanations have merit, this piece will show that the reality of the deepening US intervention in Syria is much more in tune with Trump’s original pre-election views than the handful of clashes may superficially suggest, and that, therefore, these factors cannot adequately explain the evolving policy of the Trump administration.

Divisions within the Trump administration?

While the divisions over a great many issues in the Trump regime are hardly a secret, virtually none of this has ever been related to Syria policy.

What we can schematically call the ‘Trump side’ on the question of Putin and Assad has, in any case, always had a substantial presence, despite constant changes, from former chief advisor from the “alt-right”, Steve Bannon, with his ideological affinity for Putinism shared by Trump’s first National Security Advisor, Michael Flynn, an open Putinist stooge, and his deputy NSA KT McFarlane, who advocated Putin be given the Nobel peace prize; to Secretary of State Rex Tillerson with huge economic connections to Russian business, and others like Trump’s son Donald Jnr and son-in-law Jared Kushner with own Russian connections; and Trump’s Attorney-General, Jeff Sessions, who probably combines far right ideological leanings with his own Russian connections.

On the other side, it is often claimed that Defence Secretary James Mattis, Flynn’s replacement as National Security Advisor, HR McMaster, and others in the Defence/Security establishment are traditional Russia and/or Iran hawks; UN ambassador Nikki Haley is generally slotted in here. Trump also has strong support among a number of former leaders, like Newt Gingrich and Rudy Giuliani, who in their time were considered to be traditional Republican “Russia hawks.” Somewhat less convincingly, it is sometimes claimed that vice-president Mike Pence is more hawkish than Trump on Syria.

A left-wing version of this is has it that those leaders who represent the broader interests of US capital in its rivalry with Russian imperialism are in conflict with the narrow Russian-connected business interests of Trump’s circle.

Of course, many in the Defence/Security establishment and other traditional Republican circles may well be embarrassed by the somewhat shameless way in which the Trump coterie has indulged Putin. In reality, however, when we look at the stronger positions many of these leaders have expressed about Russia, it has been overwhelmingly about the East Europe-Ukraine-NATO theatre, not about Syria. For example, after Trump refused to clearly state his commitment to NATO’s Article 5, on mutual self-defence of members, during his Europe trip in May, Mattis stepped in to strongly endorse the article. In other words, there is no dispute that US-Russian rivalry exists and that many US leaders express more anti-Russian views than Trump, but it is virtually impossible to demonstrate that this has any bearing on Syria.

Mattis is a clear case: he has always opposed “no fly zone” plans over Syria, and he opposed Obama’s threat to strike Syria in 2013 over Assad’s chemical attack on East Ghouta, claiming it did not involve US interests, and more recently declared the time to support Syrian rebels fighting both Assad and ISIS “had passed.” In McMaster’s past statements there is little of note about Syria, but he came out with the most conciliatory statements after Trump’s strike on Assad’s airbase (see below). While Haley, conversely, came out with very anti-Assad statements at that point, just days earlier she had issued perhaps the most conciliatory statement towards Assad to date, just before his chemical attack at Khan Sheikhoun.

Coming from the Christian right camp, vice president Pence does not belong in this camp at all; the only reason some consider him ‘tougher’ on Assad was due to some remarks he made during last year’s vice-presidential debate, when put on the spot about the horror then taking place in Aleppo; even then went out of his way to stress he was only talking about civilian protection, not about confronting Assad. The Christian right on the whole is ideologically inclined to be as ‘Trumpist’ as Trump on Syria (former presidential candidate Ted Cruz being a good example).

As for past leaders now in the Trump camp, Gingrich strongly opposed Obama’s threat to strike Syria in 2013, declaring “both sides in Syria are bad. One side is a brutal dictator, and the other includes Islamists and terrorists who are dangerous already and who would be brutal in power if given the chance.” Giuliani reacted to Russia’s annexation of the Crimea by stating that unlike Obama, Putin is “what you call a leader,” and compared Trump-Putin to Reagan-Gorbachev. Even the idiosyncratically hawkish John Bolton, at one point being considered for a post in the Trump administration, opposes overthrowing Assad (which he says will bring “al-Qaida” to power), even while advocating “regime change” in Iran; and to block Iran, he advocates creating a “Sunnistan” in eastern Syria where ISIS is defeated, to be led by Kurdish forces, leaving western Syria (where the anti-Assad uprising was mostly taking place) to Assad; interestingly, very much the current de-facto US-Russian agreement (as will be explained below).

The various tendencies and increasingly new versions of the Trump regime can be described as a mix of right-wing ideologues with a fascination for Putin, leaders with Russian business connections, anti-Islam warriors and a group of ‘muscular realists’ in the defence and security establishment. While there are no liberal interventionists, nor are there any “neo-conservatives”, essentially a dead species; to the extent that they make background noise, they are divided on Syria in any case, with some such as Leslie Gelb and Daniel Pipes advocating alliance with Assad.

Therefore, there is no dissension within the Trump regime on Syria, and, aside from the odd permanent internal oppositionist such as John McCain, essentially none within the Republican Party as a whole.

Drifting into confrontation with Iran … in a very strange way?

The second issue, Trump’s fierce anti-Iranian rhetoric, is a clear example of the need to distinguish between “wars of rhetoric”, which have their own uses, and what is actually happening in the region. To date, little of the rhetoric appears to have any practical application whatsoever. Yes, Trump when visited Saudi Arabia he repeated the stock phrase that Iran was the number one supporter of “terrorism” in the region. This pleased his Saudi hosts and Trump scored a fabulous US arms deal.

Yet in terms of practical impact in the region, Trump’s visit was closely followed by Saudi Arabia and a group of allies (United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Bahrain and others) using Trump’s “anti-terrorist” endorsement to slap a siege on Qatar, a key supporter of the Syrian rebels who fight against Assad and Iranian interests in Syria.

For months and months, the US and Iran, and the Iraqi regime – an asset which these two supposedly hostile powers regard as an ally – laid siege to the ISIS stronghold of Mosul. The city has been completely destroyed, “bombed back to the Stone Age,” up to 40,000 people killed, and finally this US-Iranian “regime change” operation was successful. Meanwhile, Iranian-backed and armed Shiite sectarian militia known as Hashd al-Shaabi, or Popular Mobilization Units (PMU), have poured in and are carrying out a horrific vengeance against the Sunni population, murdering, torturing, throwing them off cliffs, drowning them in rivers, in an ISIS-like orgy of sectarian terror.

This most major of all US military operations at present does not look a lot like a US-Iranian confrontation. These very same Iranian and Iran-backed Iraqi militias have been operating in Syria for years as death squads for the Assad regime, and given that the PMU is actually recognized as part of the Iraqi regime army, this effectively constitutes a pro-Assad invasion of Syria by some 20,000 troops of the US-backed Iraqi regime. While the US has been bombing Sunni jihadist forces in Syria for several years, again with a massive intensification the last few months under Trump (see below), these Shiite jihadist forces have never been hit. We will get to the significance or otherwise of the three small recent hits on them (out of 9000 US airstrikes) in the southwest desert below.

In Lebanon, Hezbollah’s close ally, the Christian rightist Michael Aoun, has recently taken over the presidency, backed by other traditional rightist forces. In recent weeks, the allied forces of the Lebanese Army and Hezbollah have launched a brutal military operation against Syrian refugees in Arsal, mostly Sunni refugees from Hezbollah’s sectarian cleansing of western Syria, where Hezbollah has created a “pure” region linking Damascus to Lebanon. Up to 18 refugees were shot, including an amputee shot in front of his family, in a Lebanese Army attack just before the onset of the larger operation; the army then arrested dozens, of whom between five and ten were tortured to death. Hezbollah has demanded the refugees be deported back to Syria, obviously not to the part it expelled them from, but probably to the new dumping ground/kill zone of Idlib. Now US Special Forces in Lebanon are operating on thê ground providing training and support to the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) working “in close proximity to Hezbollah” in the war against ISIS in the Syria-Lebanon border region. The LÀF is the 5th largest recipient of US arms in the world, and given the fact that Hezbollah has openly paraded American-made M113 armored personnel carriers on the Syrian battlefield, the possibility that the LAF is partially a conduit to the arming of Hezbollah seems highly plausible.

It is true that Trump is aiding the Saudi air war in Yemen, where the enemy is mostly the pro-Iranian Houthis allied to the forces of former dictator Saleh. But the US was already doing this under Obama. However, Trump has intensified the parallel US air war against villages controlled by Al-Qaida of the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), not against Saleh-Houthis; there have been more than 80 strikes against AQAP since February, double the number of the whole of 2016. And like in Iraq and Syria, this has gone hand in hand with a significant rise in civilian killings. And now US special forces are on the ground supporting UAE troops in a major offensive against AQAP.

Thus the expected radical shift against Iranian interests simply has not materialized, and is unlikely to unless Trump decides to break with fourteen years of US policy in Iraq, the largest and most strategic of the countries discussed above.

Mattis was commonly referred to as an “Iran hawk” before the elections and he is also fond of the “world’s biggest supporter of terrorism” stock phrase. But when Trump was making noises about ripping up the Iran nuclear agreement, it was Mattis above all who insisted that this would not be done. He also stresses that change in Iran can only come about “internally,” differentiating himself from any “neoconservative” illusions that may still be around in some odd dejected pockets of the US foreign policy elite.

Given the grotesque crisis the Trump regime is in, it is not out of the question that Trump may at some stage decide to create some “war distraction” for the masses, by striking Iranian missile sites for example, “putting some meat into the rhetoric” when needed. The discussion above however suggests that if any such attack did take place, it would have little relation to current US policy in the region; the more detailed discussion below will show that it would have no relation to US Syria policy.

The fact that such a hypothetical strike would likely be driven by domestic “bread and circuses” concerns rather than any drift in US policy or “rivalry” with Iran is further suggested by the fact that it is precisely those imagined to be “hawks” in the security establishment who appear to be holding back a personally volatile Trump. In July, for the second time, Trump recertified Iran’s compliance with the 2015 nuclear deal, but this followed an hour-long meeting where “all of Trump’s major security advisers” – Tillerson, Mattis, McMaster, and Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff, General Joseph Dunford – recommended recertification despite Trump spending “55 minutes of the meeting telling them he did not want to.” McMaster’s dismissal of leading Iran-hawk, Derek Harvey, from the NSC may also better underline the direction of the US government than a bunch of Trumpist rhetoric.

Inter-Imperialist Rivalry?

The third argument – that the creeping victory of Assad over the revolution removes an obstacle to all these global and regional rivals from clashing with one another – is more persuasive, and based on sound premises. Despite tactical differences on how to do it, destroying the revolution one way or another was one thing that united these various powers. Now, any clashes that may erupt would have even less connection with the question of revolution and counterrevolution than at any time before.

However, there are two points here. The first is that, yes, Assad has the upper hand in the military struggle against the revolutionary forces at present, but whether or not it is all over remains to be seen. The fact that the present reality does not yet indicate any approaching clash between rival global and regional powers may well indicate that the death forecasts are premature.

But even if for argument’s sake we say it is all over, this present reality indicates that while the end of the revolution would remove an obstacle to such clashes, it does not follow that such clashes are inevitable. There is, of course, always rivalry at some level between various imperialist and capitalist powers. But capitalist rivalry does not always lead to conflict; in reality this is only sometimes the case.

Of course, I have no crystal ball and events may prove this wrong. Mistakes, accidents, minor clashes over tiny bits of ground, conflicts over “credibility”, or the actions of wild cards, all have the potential to blow a situation out of control despite anyone’s intentions. And if my predictions are wrong, and the end of the Syrian revolution did lead to the Trump regime feeling free to launch an attack on Iran, for example, such a war should indeed be recognized as naked imperialist aggression with no connection to Iran’s bloody role in the crushing of the Syrian people, which the US has facilitated. At present, however, the current US role, as discussed in the section above, would appear to make this an unlikely eventuality.

The argument here is that there is no appetite for any serious conflict over Syria; there is little fundamental the powers would want to fight over anyway (conspiracist nonsense about “gas pipelines” notwithstanding); and that the main desire of imperialist and regional powers is to restore some kind of capitalist stability to the region, necessitating compromises. A Dayton-style regional deal is more on the cards than a new war.

Strikes on Assad: Entirely circumstantial

Furthermore, regarding the idea that the five or so clashes between the US and Assadist or pro-Assad forces indicate a new trend, a drift in the direction of some future war, I suggest that on the contrary they have all been entirely circumstantial. The only “trend” one might discern is a greater concern to enforce “red lines” than Obama showed, but even that is debatable. If anything, these minor clashes and clearer red lines are making the main game – all that is allowable within these “lines” – also much clearer: a US-Russia alliance, a victory for Assad, an enormous joint massacre within ISIS-held territory, a division of the spoils, and an abandonment of all pretenses of supporting any democratic transition in Syria.

It is also useful to place these five US-Assadist pinprick clashes in context; these first few months of the Trump regime have seen a far more massive intensification of the US war on ISIS, including a very dramatic rise in civilian casualties: the number of civilians killed by US bombing in Iraq and Syria in Trump’s first six months is now higher than the number of civilians killed in Obama’s eight years, including 472 killed by US airstrikes in Syria between May 23 and June 23 alone, the third month in a row that civilian casualties from US strikes topped even Assad’s toll. The figures for Iraq in particular are likely to be massive underestimates, with evidence of a death toll as high as 40,000 from the battle of Mosul; meanwhile, the real civilian toll from the decimation of Raqqa is likely to be much higher than current figures suggest, and by the time of writing in late August, enormous massacres are occurring daily, for example, 158 civilians killed between August 18 and 22.

From any human point of view, a comparison between the US bombing of a mosque in Idlib in March (allegedly targeting Nusra), where 57 worshippers were killed, and the US strike on the Assadist air base a few weeks later, highlights what a mundane event the second was, even ì only the second drew the ire of the alleged “anti-war” movement in the West.

So, while the five clashes with Assadist forces in six months might seem like a lot compared to none in six years, we are talking about microscopic numbers compared to the gigantic US assault on ISIS, on Nusra, on Idlib, Raqqa, Deir Ezzor and Mosul, and above all the civilian populations of these places. When these five strikes are placed alongside the actual war trend under Trump, it demonstrates that they are not indicative of any trend at all.

The Shariyat strike and its aftermath

Did the US bombing of Assad’s Shariyat airbase in April – the first US hit on Assad after nearly 8000 US strikes in Syria at that point – signify a new US policy?

Not even remotely. In the very weeks before Assad’s chemical massacre in Khan Sheikhoun, three prominent US leaders made Trump’s pro-Assad position even clearer. US UN representative Nikki Haley announced that the US was “no longer” (sic) focused on removing Assad “the way the previous administration was”; Tillerson used Assad’s very words, declaring that the “longer term status of president Assad will be decided by the Syrian people”; and White House spokesman Sean Spicer declared that “with respect to Assad, there is a political reality that we have to accept.”

When Assad took all this encouragement to mean that even sarin could be legitimised, the US had little choice but to strike Assad for the sake of its own “credibility.” The whole point of the US back-down on its “red line” in 2013, after Assad had slaughtered 1400 with sarin in East Ghouta, was that it was exchanged with the “victory” of getting Assad to remove all his sarin, an arrangement facilitated by Putin and Netanyahu. In demonstrating not only that he was still keeping some sarin despite the agreement, but also that he was willing to use it, Assad forced Trump to make a credibility strike, going against the very clear stated intentions of the entire Trump regime just days earlier.

One might say this shows that Trump at least enforces “red lines” more than Obama. But in reality, it was Obama’s deal with Assad and Putin that created the necessity of a strike this time: Assad had simply not used sarin again (at least in any large enough display to get media attention) during Obama’s reign, so we cannot make any assumptions about what may have happened (though of course Assad has used chlorine dozens of times under both Obama and Trump).

To soften the blow, Trump gave ample warning to Russia, who warned Assad, that the base would be hit. As a result, according to the Russians, some half a dozen clapped out warplanes were hit. By the following day, the base was again in use bombing Syrians around the country, and Khan Sheikhoun was again being bombed – just not with sarin.

The follow-up, again by all wings of the regime, clarified further that for Trump, this really was a one-off. Tillerson stressed the strike was entirely about sarin and warned “I would not in any way attempt to extrapolate that to a change in our policy or posture relative to our military activities in Syria today. There has been no change in that status.” Trump stressed that “we’re not going into Syria,” but the strike only occurred because of the use of chemical weapons “which they agreed not to use under the Obama administration, but they violated it.” In other words, the US had no interest in Assad’s continued use of his other weapons of mass destruction. Mattis stressed that tensions with Russia would “not spiral out of control,” and that “our military policy in Syria has not changed. Our priority remains the defeat of ISIS,” but Assad “should think long and hard” before using sarin again. McMaster, allegedly the most “hawkish” towards Russia, clarified that if there were to be any “regime change” in Syria, it would be carried out by Russia, not the US; that the US had no concern that the base was being used again the next day, as harming Assad’s military capacities was not the aim of the strike; and that the US goal remained defeating ISIS while it also desired “a significant change in the nature of the Assad regime and its behavior in particular.”

So, for all the thousands of pages that have been written about the US aiming for “regime change” in Syria, it turns out that the ‘hardest’ policy within the Trump regime, at the tensest moment, was for “regime character change” under Assad, facilitated by Russia.

The downing of an Assadist warplane

What then of the fact that the US shot down an Assadist warplane near Tabqa, in Raqqa province, on June 18, for the first time in the 6-year Syrian war – does this represent a new policy direction?

In fact, once again there was little change. For six years, the Assad regime has bombed cities and towns held by the rebels all over Syria, reduced everything to rubble, killed hundreds of thousands, and there has never been a US move to down a single Assadist warplane even to defend civilians, or schools, or hospitals, let alone rebel fighters. In fact there has been a US-enforced embargo on the supply of anti-aircraft weapons to the rebels, preventing them from doing it themselves as well. Both policies continue.

Yet as soon as Assad made the highly unusual move of attacking the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the US-backed military and political front dominated by the Kurdish-led People’s Protection Units (YPG), the US shot down the Assadist plane.

The main reason the YPG/SDF has become the most strategic US ally in the conflict (the US providing wall-to-wall air cover for its operations, large numbers of US special forces, and several military bases) is that both the US and the SDF are focused entirely on defeating the Islamic State (ISIS) in eastern Syria, and neither have any interest whatsoever in fighting the Assad regime or supporting the anti-Assad rebellion. As the anti-Assad struggle is mostly centred in the more populated west of the country, the US and SDF/YPG just carry out their parallel war on ISIS in the east.

This means there is normally no reason for Assad to bomb the SDF/YPG. The attack this time came as the US/SDF were besieging the ISIS capital Raqqa, when Assad’s forces broke out of southeastern Aleppo to advance on Raqqa themselves. A conflict over the mopping up operation against ISIS. The US defence of its allies thus had no connection one way or another to the question of the anti-Assad revolution.

But even from the point of view of “red lines,” once again the action was set by the Obama administration, which announced its first and only No Fly Zone in Syria in the Kurdish-dominated parts of northern Syria known as ‘Rojava’, controlled by the YPG/SDF, in August last year. At that time, Assadist jets suddenly decided to do a little unprovoked bombing of the YPG in Hassakah, apparently just to remind the YPG who was boss.

The US warned the Assadist warplanes to keep away or they would get bombed. They ran away fast. They did not try again under Obama. Now they tried again under Trump, to see if Obama’s NFZ still applied. They learnt that it did. But bombing everywhere and everyone else in Syria continues, and Assad knows not to expect any problem from Trump with that.

The US Centcom statement on the downing of the warplane emphasised that its mission is only to defeat ISIS and that it has no interest whatsoever in fighting Assadist, Russian or pro-regime forces, but that it will defend itself or its “partner forces.”

Still, was this at least a sign of the growing conflict between the rival camps? Of course, the fact of a hit demonstrates that clashes can occur. That it has not re-occurred in that theatre is just as important; according to embedded journalist Robert Fisk, a “coordination centre” has been set up in the east to prevent “mistakes” between “Russian-backed and American-supported forces,” as “all sides are determined to avoid any military confrontation between Moscow and Washington.” As we will see below, this may also involve a US-Russia agreement on how to divide the spoils in the ISIS-held east.

The conflict in the southeast desert

The other three US hits between mid-May and early June, on Iranian-backed, pro-Assad Iraqi militia, all took place within a 55 square kilometer patch of desert around a US base in al-Tanf, a town wedged into the corner where the Syrian, Iraqi and Jordanian borders meet.

Do these three micro-hits in this tiny region signify that Trump is “taking up the Iranian threat to the region” and proving to the Saudis and others that he is on their side? What a laugh.

The US presence at al-Tanf began when the Pentagon set up the New Syrian Army (NSA) in 2015, as a brigade that would specifically fight ISIS only and not the regime. However, as such a fight does not attract many rebels, the NSA seemed to disappear. But in the meantime, the US and Jordan were putting enormous pressure on a real mass FSA formation – the powerful Southern Front – to stop fighting Assad and to only fight ISIS and Nusra. So while the southern front against Assad went quiet, the US quietly assembled two new brigades in al-Tanf, Maghawir al-Thawra (MaT), or the Commandos of the Revolution, and Shohada al-Quartayn. It is unclear whether they were previously part of the NSA, or former cadres of the Southern Front, but neither are currently members of the SF. They appear to have crossed into southeast Syria from Jordan, following CIA training and vetting to ensure they do not fight Assad (though as discussed above, Shohada al-Quartayn has now quit for precisely this reason).

Looking at a map, it is striking how distant al-Tanf is from the centres of revolutionary conflict in western Syria. And notably, while the headlines featured these microscopic clashes in the distant desert, the Assad regime was conducting a major murderous offensive against the revolutionary stronghold of Daraa in the southwest. There were of course no US hits over there to defend the FSA or the Daraa citizenry.

The US base at al-Tanf is where the Pentagon works with these brigades in its war on ISIS. To facilitate this work, it declared a 55 square kilometre zone around it as a “de-confliction zone” (in line with the de-confliction zone policy being pushed by Russia, Turkey and Iran). This meant there were to be no clashes between the US-backed forces and nearby pro-Assad forces, so that they could all focus on fighting ISIS.

All three strikes on the Iranian-backed forces have been inside this very small pocket of desert. In each case, the strikes only took place because the Iranian-backed forces were advancing against the US-backed forces rather than against ISIS.

In every case, the US-led Coalition’s ‘Operation Inherent Resolve’ released an almost identical statement, which stressed that although it had acted against these forces advancing towards the US base inside the zone, with seemingly hostile intent,

“The Coalition does not seek to fight the Syrian regime, Russian or pro-regime forces partnered with them. … The Coalition presence in Syria addresses the imminent threat ISIS poses globally, which is beyond the capability of the Syrian regime to address. … The garrison is a temporary Coalition location to train vetted forces to defeat ISIS and will not be vacated until ISIS is defeated. … Coalition forces are oriented on ISIS in the Euphrates Valley. The Coalition calls on all parties to focus their efforts in the same direction to defeat ISIS, our common enemy and the greatest threat to worldwide peace and security.”

This seems pretty clear. One might argue that this is just window-dressing, that really the US presence in al-Tanf is aimed precisely at fighting Iran. But in that case, would we not have seen more than three pin-prick strikes, and not only restricted to this tiny patch of desert in the furthest corner of Syria?

In any case, other events here revealed the limitations of US aims in that region.

First, when these US-backed brigades, or other FSA forces, have been operating outside the zone and are confronted by Assadist forces, the US has not helped them. In fact, Assad’s forces took advantage of the US and MaT focus on fighting ISIS only, and the continued US-Jordanian freeze on the Southern Front, to seize significant parts of the eastern Qalamoun and eastern Suweida regions from the rebels, but these brigades was not allowed to link with the FSA in east Qalamoun, with some reports claiming the US promised to cut their pay and arms if they did so:

“As opposition forces battled IS fighters farther east over the weekend, pro-regime soldiers attacked the overstretched desert rebels roughly 60km southwest of the ancient city of Palmyra, … The regime’s assault led to a swift victory. … On Monday, rebel sources told Syria Direct that the US-led coalition provides financial and logistical support for opposition forces to combat IS but stops short of funding the rebels to directly attack the regime. “The coalition is a partner of ours in the war against Daesh [the Islamic State], but when it comes to fighting the regime and its foreign militias, [the coalition] is not our partner,” Al-Baraa Fares, a MaT spokesman, explained.

Perhaps even more stunningly, the US has even given permission to the Assad regime to bomb inside its exclusion zone. On June 6, the Assad regime relayed a request to the US military via Russia to bomb the US-proxy forces inside the US-declared zone, because they were attacking Iranian-backed forces operating just inside the zone. So, even though the US itself demands these pro-Assad forces not enter the zone, it does not give permission for its own proxies to attack them, because it only supports them fighting ISIS. So the US gave permission to Assad to bomb its (the US’s) own proxies inside its own exclusion zone! Yet later that same day, when the Iranian-backed forces refused to leave and allegedly brought reinforcements in, the US made its third (and last) trike against them.

One reason commonly cited for the US stand in al-Tanf is that the Baghdad-Damascus Highway passes through the town, and the US is thereby blocking a direct Iranian connection, a “land bridge”, to Syria, which would effectively link Iran to Hezbollah in Lebanon by land. So, even if the strikes have been few, small and circumstantial, the very US presence here fulfils an important anti-Iranian outcome.

Another factor is that Jordan aims to have a ‘safe zone’ inside Syria along its borders once ISIS is driven away. Such a zone would enable refuges to stay rather than enter Jordan, and perhaps even allow Jordan to push refugees back into Syria. Therefore, it needs a strip of border free of regime or Iranian control.

While the real reason may be a mixture – or it may even be simply a convenient place for the US to train these forces in its fight against ISIS – the anti-Iranian reason is undermined by the fact that there remains a great expanse of Syria-Iraq borderland that Iranian, pro-Iranian Iraqi and Assadist forces can seize in order to form the land bridge. If we take out the small area around al-Tanf in the southeast corner, and the northern part of the Iraq-Syria border around Hassakah, controlled by the US-backed SDF, then we are left with the entire ISIS-controlled Deir-Ezzor province.

Now, just after the third strike, around June 10, it appears that Russia mediated, and persuaded the Iranian-backed forces to leave the Americans alone in al-Tanf. Pentagon spokesman Captain Jeff Davis claimed that Russia had been “very helpful” in calming down the situation near al-Tanf, by “communicat[ing] U.S. concerns to pro-Syrian government forces in the area.”

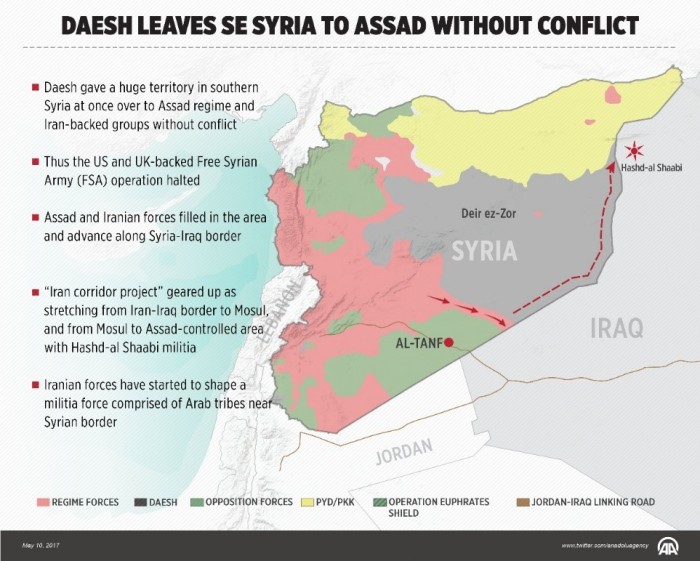

A defeat for Iran? Unclear, because Iranian-backed Iraqi militia leaders simply re-routed their land-bridge concept: as this map shows, its proposed route passes through Deir Ezzor province, via the border town of Abu Kamal and the heavily bombed – by the US and Assad in tandem – town of Mayadin.

But wait – this “re-routing” had already been declared in early May. Further, it was not being re-routed north from al-Tanf, but rather south from SDF-controlled Rojava. Perhaps Iranian-backed forces entering from Iraq had assumed they would be allowed through, due to the SDF’s sometimes dealing with Assad; but the SDF made clear that it would fight the PMU if it crossed the border into Rojava. But this suggests that al-Tanf was not the original land-bridge plan anyway, not the big deal it was made out: the micro-clashes appear to have been a mere test of waters, if not a distraction.

But then we read in countless articles that the US was aiming to seize Deir-Ezzor from ISIS and so this would likely be the scene of the great US-Assad or US-Iran show-down.

But then something else also happened on June 10: ISIS suddenly withdrew from “thousands of square meters of land” in a strip that connected Assad-controlled Palmyra with the Iraqi border, just north of al-Tanf; Assadist and Iranian-backed forces immediately filled the strip without a fight, reaching the Iraqi border, thereby cutting off the only possible land-route for US-backed forces to advance north between al-Tanf and and Abu Kamal in Deir-Ezzor province. We can see the problem on this map:

Surely now the US had to react, to prevent this new major step in the Iranian land-route project, to ensure “US-backed” forces can get Deir Ezzor? Well, not according to the Pentagon, which reacted: “We give them [FSA] training and equipment, and they fight against Daesh. That is all. We don’t help them to control an area or fight against the regime … our only focus is Daesh. We are not a part of their struggle against the regime.”

Meanwhile, Iranian-backed forces in Iraq (the PMU) had also reached the Syrian border near the southern end of Rojava, already on May 29. Having thus reached both sides of the border, the pro-Iranian forces are now poised to meet up. Not immediately – the Iraq-based forces are far north of the Syria-based forces, and what stands in between is ISIS-controlled Deir-Ezzor province.

So, as the “nightmare scenario” has almost arrived, will the US now fight tooth and nail to prevent the world’s “number one backer of terrorism” from forming its land bridge all the way from Tehran to Beirut? Meaning, specifically, the US must prevent the regime and Iran from seizing Deir-Ezzor from ISIS; even if now blocked by land, should the US be expected to use the SDF to advance south to prevent this from happening?

Leaving aside the fact that the Iranian-backed forces in Iraq are part of the US-backed Iraqi regime, a US-Iran joint venture, and that the US, Iran and these Iraqi forces have just been on the same side in a gigantic and extremely bloody war in Mosul; leaving aside the fact that the US and Assad have been bombing ISIS in Deir-Ezzor province in alliance, or at least in tandem, since November 2014, with many bloody mass casualty events, indeed that the US has protected the regime airport from ISIS siege; leaving aside the fact that US bombing directly helped Assad reconquer Palmyra earlier this year, and Palmyra is the regime’s gateway into Deir-Ezzor; surely, so the ideology goes, the US must now do everything to prevent the Iranian land-bridge.

Well, not quite.

On June 23, US-led Coalition spokesman Colonel Ryan Dillon explained that if the Assad regime or its allies “are making a concerted effort to move into ISIS-held areas” then “we absolutely have no problem with that.” Dillon said that “if they [ie, Assad regime] want to fight ISIS in Abu Kamal and they have the capacity to do so, then that would be welcomed. We as a coalition are not in the land-grab business. We are in the killing-ISIS business. That is what we want to do, and if the Syrian regime wants to do that and they’re going to put forth a concerted effort and show that they are doing just that in Abu Kamal or Deir el-Zour or elsewhere, that means that we don’t have to do that in those places.”

This could hardly be clearer; far from the US engaging in “rivalry” in resource-rich east Syria with the Assad regime, Russia or Iran, far from a great new alliance with “conservative Sunni states against Iran” and so on, especially in the most strategic province of Deir-Ezzor, rather, for the Pentagon, if Assad and allies take this region from ISIS, the US “doesn’t have to” go there. Why go there, when your allies are headed there anyway?

Indeed, despite the harsh anti-Iran rhetoric of the Trump administration, it is notable that while US bombing mainly supports the SDF, or the Tanf proxies, against ISIS in Deir Ezzor, US bombing also directed aided not only Assad’s forces but even Iran-led forces over many months in 2017.

Still, it may be surmised that the Assad regime taking Deir Ezzor does not necessarily mean this Iranian presence remains long-term, with which to build their land-bridge (since the question here is not morality – the Assad regime is far more genocidal than Iran’s theocratic despots – but the geopolitical issue of Trump’s alleged desire to “stop Iran”). It may be that a deal is done, that the US does not oppose Assad reconquering the province, as long as Iran later leaves. And to ensure this, the key would be a greater involvement of Russia.

And exactly this has supposedly been discussed: a deal by which Assad allows the US and SDF to take Raqqa, while the US allows Assad and Russia to take Deir-Ezzor, with no mention of Iran. In light of indications of Russian-Iranian rivalry – even claims that Assad is under pressure from “pro-Russian factions in his ruling circle” to dump Hezbollah, as a means of weakening Iranian influence – such a deal is quite plausible.

Yet it is doubtful that even that would change very much. Assad’s armed forces are simply so weak that they are dependent on the tens of thousands of foreign Shiite jihadists coordinated by Iran, above all the 20,000 or so Iraqi PMU fighters. Further, even if all these pro-Iranian forces were excluded, as long as Assad remains allied to Iran and Iraq, then Assadist control of Deir Ezzor ensures a geographical link between Tehran and Beirut – unless Russian troops were to actively block the border.

In other words, all indications are that the land-bridge that was supposed to be a red line is essentially US policy.

There are even indications that the Pentagon may be planning to give up even al-Tanf to Assad and Iran, just keeping some desert near Jordan’s border and the northern SDF-controlled region, thus allowing the land-bridge to proceed along the Baghdad-Damascus highway. According to some sources, the US-backed units “could be airlifted over the regime forces and ISIS to a front line near al-Shaddadi, which is held by the Syrian Democratic Forces.” As CentCom spokesman Dillon explained, al-Tanf is a mere “temporary garrison” which will not see growth, “if anything, it will be in the opposite direction.” Given that one of the US-backed brigades has quit al-Tanf and the US alliance in order to fight Assad in south Syria, and two groups of fighters from MaT have gone the other way and joined Assad’s army, it may also be that the whole US operation from al-Tanf collapses due to its own contradictions. However, this may not go down well with Saudi Arabia, as we will discuss below.

‘De-escalation’ and counterrevolution

The American acquiescence with Assad’s control of Deir-Ezzor, while trying to hang onto al-Tanf, is connected to the “de-escalation zones” process initiated by Russia, Turkey and Iran, with the US, Jordan and Israel playing back-seat roles. The Assad regime has said little about them, despite both Russia and Iran being involved; it retains its “right” to violate them even when they are in its favour, continually bombing these zones. The opposition, by contrast, has from the start slammed the process as a form of partition of Syria, yet has been forced to take part in practice.

This process sets aside a number of opposition-controlled zones where the regime and rebels are to “de-escalate”, ie, freeze the battle lines. These various foreign powers would be guarantors of these local ceasefires; as Turkish presidential spokesman Ibrahim Kalin explained, the three countries are working on a plan to station their forces in these zones, suggesting that Russian and Turkish forces could be stationed in Idlib, Iranian and Russian troops around the Damascus region, and Jordanian and US forces in Daraa. Without going into detail, anyone who follows events in Syria closely will see from these ideas what a counterrevolutionary conception this is.

Initially, four zones were laid out: the rebel-held province of Idlib and adjoining parts of Aleppo and Hama provinces; a stretch of rebel-held territory in northern Homs; the remaining rebel-held Damascus suburbs; and rebel-held parts of the south, particularly Daraa. At this stage, however, all these fronts remain active and have only barely de-escalated; and even where the zones have officially been declared, the regime continues to bomb.

Meanwhile, the US added the southeast desert region around al-Tanf as another zone, because the rebels there are only to fight ISIS and not the regime. And to much fanfare, the US and Russia declared they had successfully negotiated a de-escalation zone in the southwest, the region adjoining the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, involving Jordan and Israel. Russia has begun occupying this zone, as a guarantee to Israel that the regime’s return to the Golan “border”, which Israel is in principle in favour of, is not coupled with Iranian or Hezbollah presence; under the agreement, Iranian-backed forces have to keep out of this zone. Russia has also occupied rebel-held southern Daraa, and deployed its forces in the new de-escalation zone, negotiated via Assad’s Egyptian ally, in rebel-held East Ghouta, likewise signaling the regime’s return by stealth; and Egypt was again brought in to help broker the Homs de-escalation zone; this Egyptian involvement is a powerful link between the interests of Assad, Israel, Russia and Saudi Arabia.

In addition, the rebel-held region of northern and eastern Aleppo province where Turkish troops are present as part of the Euphrates Shield operation is effectively a de-escalation zone, as the rebels there only fight ISIS and are not permitted to confront the regime (and, at least in this case, it also means they are free from regime bombing); and the ‘Rojava’ region under SDF control and US protection, stretching from Manbij to Hassake (as well as the Russian-occupied Afrin pocket in the northwest corner) can also be considered such a zone, because it is likewise only at war with ISIS, and neither confronts, nor is bombed by, the regime.

At present there is much talk of a counterrevolutionary agreement between Russia, Turkey and the regime, directed at both the SDF in Afrin and HTS in Idlib. According to one scenario, Russia, which has troops protecting the SDF-held region of greater Afrin, would withdraw from some areas to allow Turkey to help its FSA allies to re-take the Arab-majority Menaq-Tal Rifaat region, which was conquered from the rebels by the YPG, with Russian airforce support, in early 2016. In exchange, Turkey would use this as passage into Idlib to attack HTS, and facilitate the entry of Russian troops into Idlib to occupy the “de-escalation zone” alongside Turkey. While the FSA would probably go along with recovering their occupied territories, it would be quite another thing if they were to go along with more ambitious Turkish plans to seize Kurdish-majority Afrin itself. It is also unclear whether the rebel groups working with Turkey in Idlib would go along with a frontal attack on HTS, if on behalf of an impending Russian occupation, regardless of their own ongoing conflict with HTS in Idlib. For its part, Russia has put it to the SDF that if it does not want to be conquered by Turkey, they need to allow a return of the regime to Afrin.

Meanwhile, while the US has not been bombing Idlib the last few months, as it focuses on the east, it is now using the HTS presence to justify any impending Russian attack on the province, despite Russia’s well-documented use of the “attacking al-Qaida” trope to bomb all Syrian rebels. “In the event of the hegemony of Nusra Front on Idlib, it would be difficult for the United States to convince the international parties not to take the necessary military measures,” State Department Syria official Michael Ratney stressed, warning rebel groups to move away from HTS before it was “too late”.

Much more could be said of what these zones and these various conflicts around their implementation mean for revolution and counterrevolution, but that would be beyond the scope of this piece. However, this ‘pacification’ program, in the context of the regime having the upper hand, is the prime means by which the global imperialist and local reactionary intervention aims both to extinguish the revolution and also “equitably” partition the spoils, partially in order to avoid the much warned about imminent conflict.

US policy in the east fits firmly into this context. Regarding the global imperialist powers, the US-Russian partition of Syria is reasonably clear: Russia, via its tool in Damascus, is in control of most of western Syria (“useful Syria”), and the US, with its allies (SDF) and proxies (MaT or others) controlling much of the east. Russia’s new 50-year agreement for its air base in Latakia, simply highlights the fact that the US has never appeared to have any objective of trying to eject Russia from its bases on the Mediterranean; other than in the most conspiracist literature, there has simply never been any suggestion that this had any relation to US Syria policy.

At the same time, it is quite true that this process is unlikely to be smooth, and that real regional rivalries and obstacles will hamper its easy execution.

While the thesis here downplays the idea of global imperialist conflict in Syria, and also the vague idea of “rivalry” between global and regional powers, a more solid case can be made regarding rivalry between these regional sub-imperialist powers of similar size themselves, especially Saudi Arabia, Iran and Turkey (with its Qatari ally).

Defeating ISIS in the Sunni east and replacing it with some kind of local Sunni-based authorities, without Iran, appears to be a fundamental Saudi interest, giving them some influence in post-revolution Syria. This coincides with its ally Jordan’s desire to have a “safe zone” on its border to keep out refugees. Thus the strip of desert along Jordan’s border currently controlled by US-backed militia, ending in al-Tanf, would appear to be a step along this path. But with apparent US acquiescence to regime control of strategic Deir-Ezzor, meaning the fulfilment of the Iranian land-bridge, a rather large gap is thus driven through the concept of a US-controlled east Syria where Saudi interests could balance Iran. Whether the proposed Russian occupation of a regime-controlled Deir-Ezzor would satisfy Saudi Arabia that Iran could be kept out seems uncertain, despite excellent Saudi-Russian relations. Interestingly though, this Saudi interest in the east, while the Saudi-led bloc feuds with Turkey’s ally Qatar, has created potential for an ideologically odd rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and the US’s SDF allies controlling the northern part of east Syria.

The issue of the Iranian land-bridge could also be undermined by other factors, above all the fact that both Deir Ezzor province, and the Iraqi side of the border opposite Deir-Ezzor, namely Anbar province, are overwhelmingly Sunni. The Iraqi regime and PMU will need to control Anbar to effectively link with an Assad-controlled Deir Ezzor, but Anbar was the heartland of the Sunni-led insurgency against the US occupation from 2003 onwards. How the locals will take to being ruled by sectarian Shiite forces remains to be seen, but that is connected to the entire question of what a post-ISIS Iraq will look like now that ISIS has been defeated. Moreover, the US ceding of Deir-Ezzor to Assad may be no guarantee of smooth sailing there either; Deir-Ezzor was an early centre of the anti-Assad uprising. The FSA’s Unified Military Council of Deir-Ezzor was founded on March 19 with the aim of unifying efforts to liberate Deir-Ezzor from both ISIS and the regime; important brigades formed by Deir Ezzor locals, such as Jaysh Assud Al-Sharqiyah, are operating in the southeast to block Assad’s advance into Deir Ezzor, which they claim will be liberated “by its sons.” Moreover, as the opposition site Enab Baladi Online explains, “the tribal population [of Deir-Ezor] have strong ties with Saudi Arabia, which sees control of the area as strategic to counterbalancing the Iranian Shiite influence.”

Other issues involving Israel, Hezbollah, Turkey and the Kurds have already been noted above. Yet whichever way we look at it, the overall US-Russia agreement appears to guarantee a chunk of Syria for everyone. Aside from the guaranteed US and Russian zones, Israel gets to keep its Golan theft, if not effectively extend it somewhat; Turkey gets to keep the Azaz to Jarablus strip, regardless of the fall-out of the current dealing in Afrin and Idlib; even if Iran does not get its land-bridge fully intact, it still gets to keep the “cleansed” Qalamoun region linking Damascus to Lebanon and to the Alawite coast and Homs, as long as its Hezbollah allies don’t venture too far south; and Jordan gets to effectively control a strip of pacified southeast Syrian desert as a buffer.

It goes without saying that such an arrangement may well break down, and that such unjust “peace” agreements are often creators of future wars. But we can also confidently say that the revolutionary wave that began in the Arab Spring is not over, despite its setbacks in Syria and elsewhere – see the current uprising in Morocco’s Rif for example – and will continue to threaten the “stability” enforced by the regional soft-partition being enacted. The various imperialist and local reactionary powers, however much some may hate each other, will continue to be confronted by situations which force them into unwritten alliance against the masses of the region.

Reblogged this on Taking Sides.

Thankks for sharing this